Sample 15555r

15555 Olivine-normative Basalt 9614 grams

Section titled “15555 Olivine-normative Basalt 9614 grams”

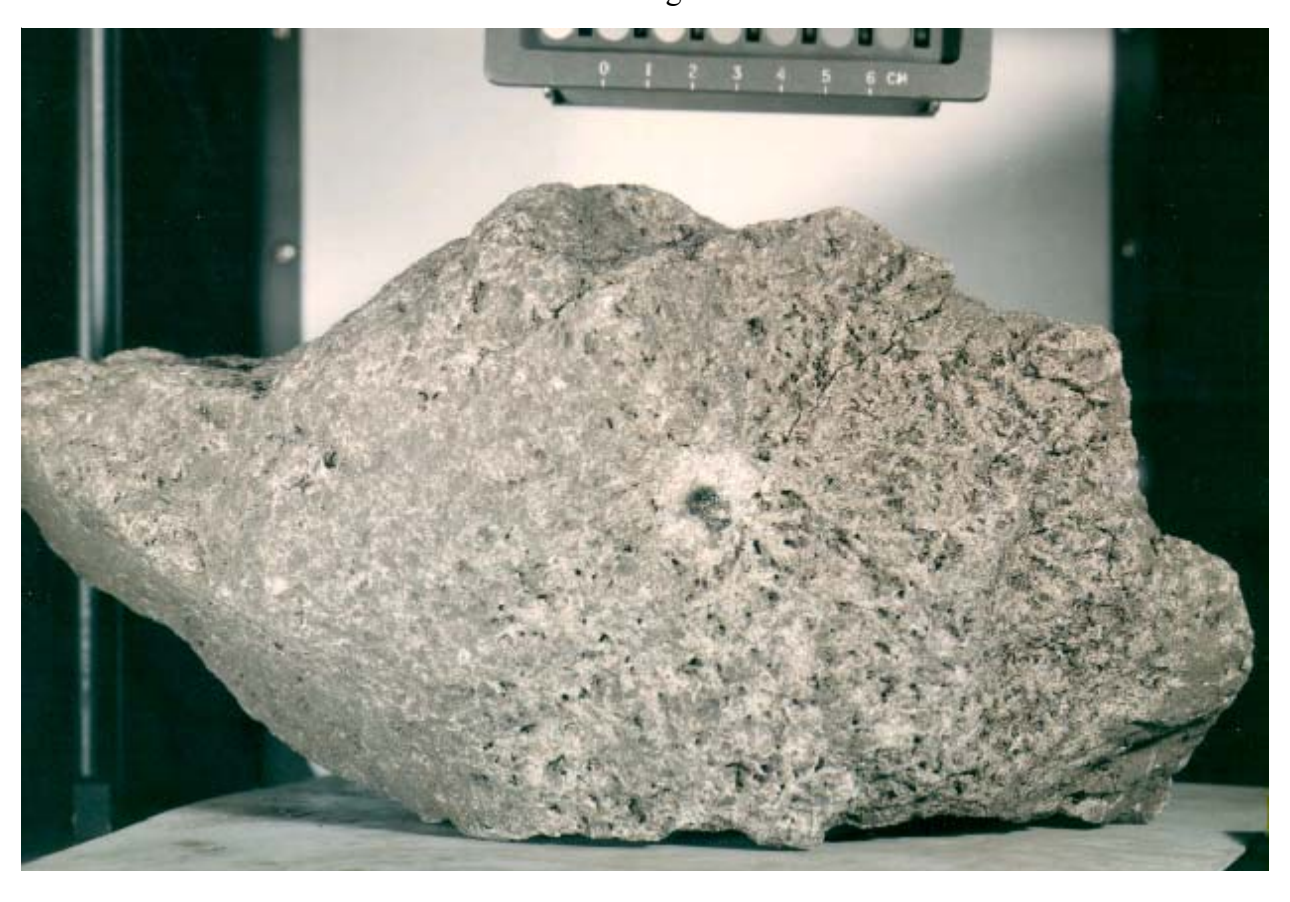

Figure 1: Photo of S1 surface of 15555, illustrating large mirometeorite crater (zap pit) and vuggy nature of rock. NASA S71-43954. Scale is in cm.

Introduction

Section titled “Introduction”Lunar sample 15555 (called “Great Scott”, after the collector Dave Scott) is one of the largest samples returned from the moon and is representative of the basaltic samples found on the mare surface at Apollo 15. It contains olivine and pyroxene phenocrysts and is olivine normative in composition (Rhodes and Hubbard 1973, Ryder and Shuraytz 2001). The bulk composition of 15555 is thought to represent that of a

primitive volcanic liquid and has been used for various experimental studies related to the origin of lunar basalts (e.g. Walker et al. 1977).

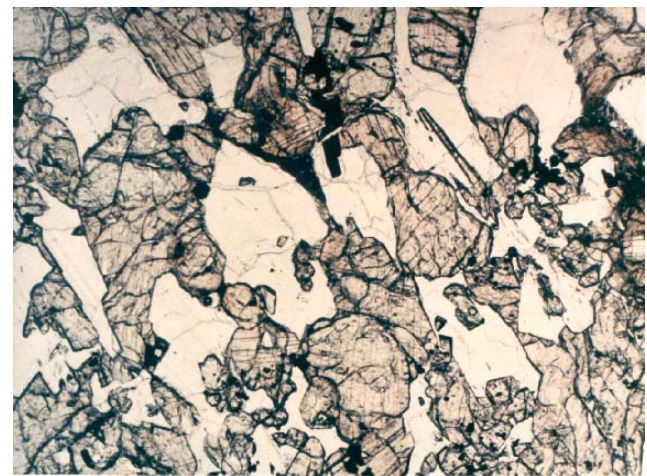

15555 has a large zap pit (~1 cm) on the S1 face, various penetrating fractures and a few percent vugs (figure 1). It has a subophitic, basaltic texture (figure 4) and there is little evidence for shock in the minerals. It has been found to be 3.3 b.y. old and has been exposed to cosmic rays for 80 m.y.

| Mineralogical Mode of 15555 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longhi et al. 1972 | McGee et al. 1977 | Heuer et al. 1972 | Nord et al. 1973 | |||||||

| Olivine | 12.1 | 5-12 | 20 | 20 | ||||||

| Pyroxene | 52.4 | 52-65 | 40 | 40 | ||||||

| Plagioclase | 30.4 | 25-30 | 35 | 35 | ||||||

| Opaques | 2.7 | 5 | ||||||||

| Mesostasis | 2.3 | 0.2-0.4 | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| Silica | 0.3-2 |

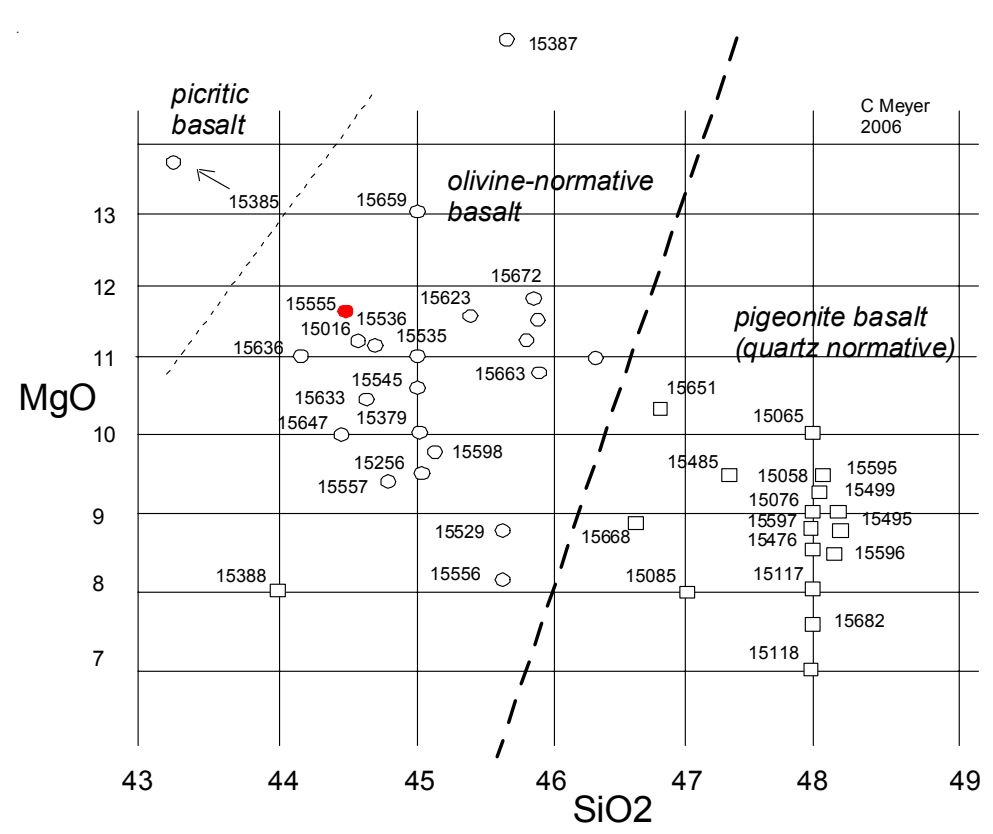

Figure 2: Composition diagram for Apollo 15 basalts (best data available) showing two basic types. The olivine-normative samples have been shown to be related to one another by olivine addition or subtraction but can not be related to the pyroxene-phyric basalts (see Ryder and Shuraytz 2001).

Ryder (1985) carefully reviewed all aspects of 15555. It is one of the most allocated and most studied samples from the moon and it has often been used in public displays.

An aside

Section titled “An aside”The Apollo 15 basalts were all found to be the same age and therefore related in space and time. They also all have the same trace element content, but they were found to have either high or low silica contents (figure 2). In this compendium, the high silica basalts will be referred to as Pigeonite Basalts, because they have abundant pigeonite phenocrysts, and the lower-silica group as Olivinenormative Basalts. When carefully analyzed, the olivinenormative basalts could be related along an olivine fractionation line (Ryder and Shuraytz 2001). Two small, friable, coarse-grained samples are enriched in olivine (15385, 15387) and one sample (15065) has a region that is apparently enriched in mafic minerals. These rocks have notable variations in texture and mineralogy due to different gas content (vesicles and vugs) and cooling history (some have glassy matrix).

Petrography

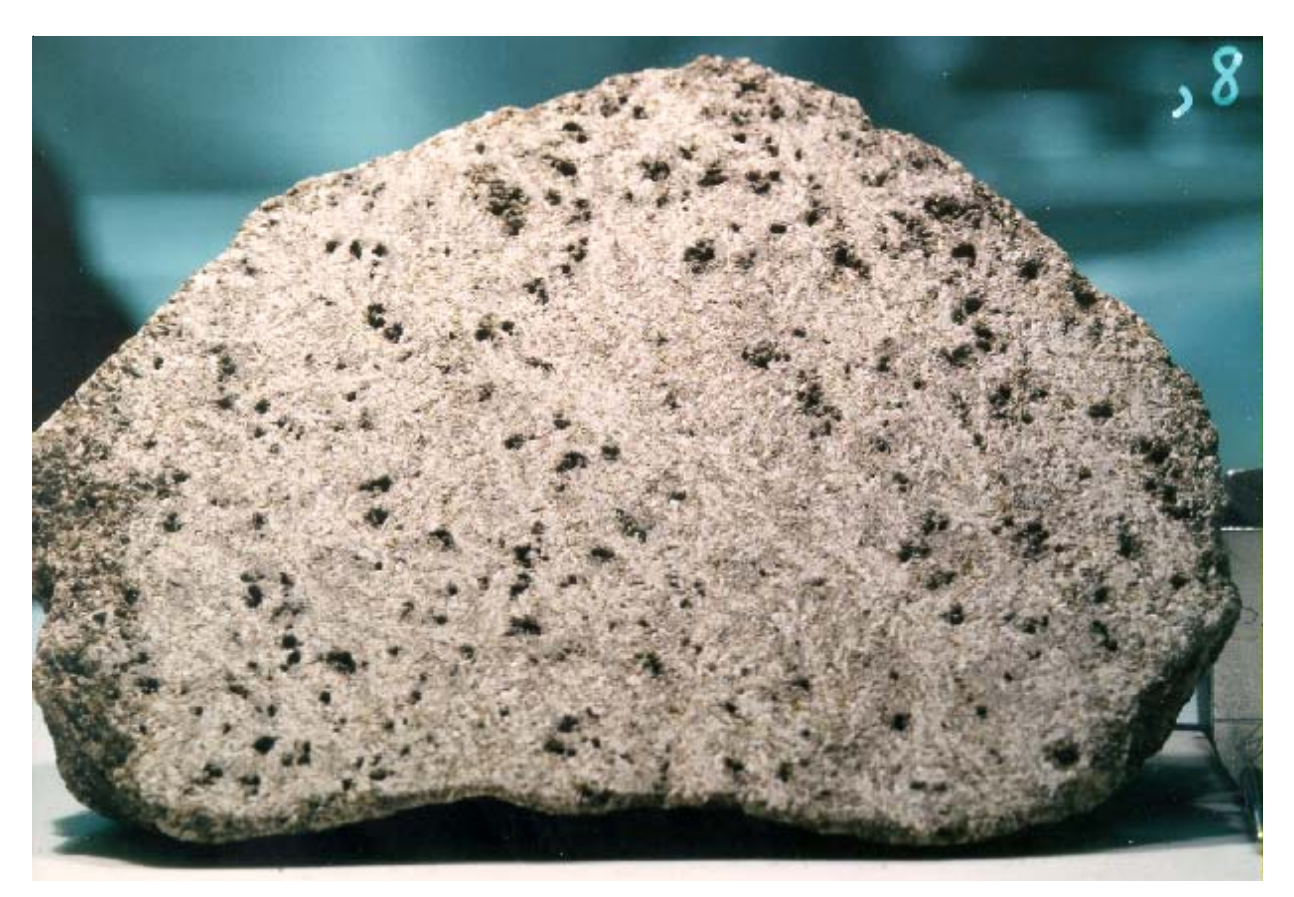

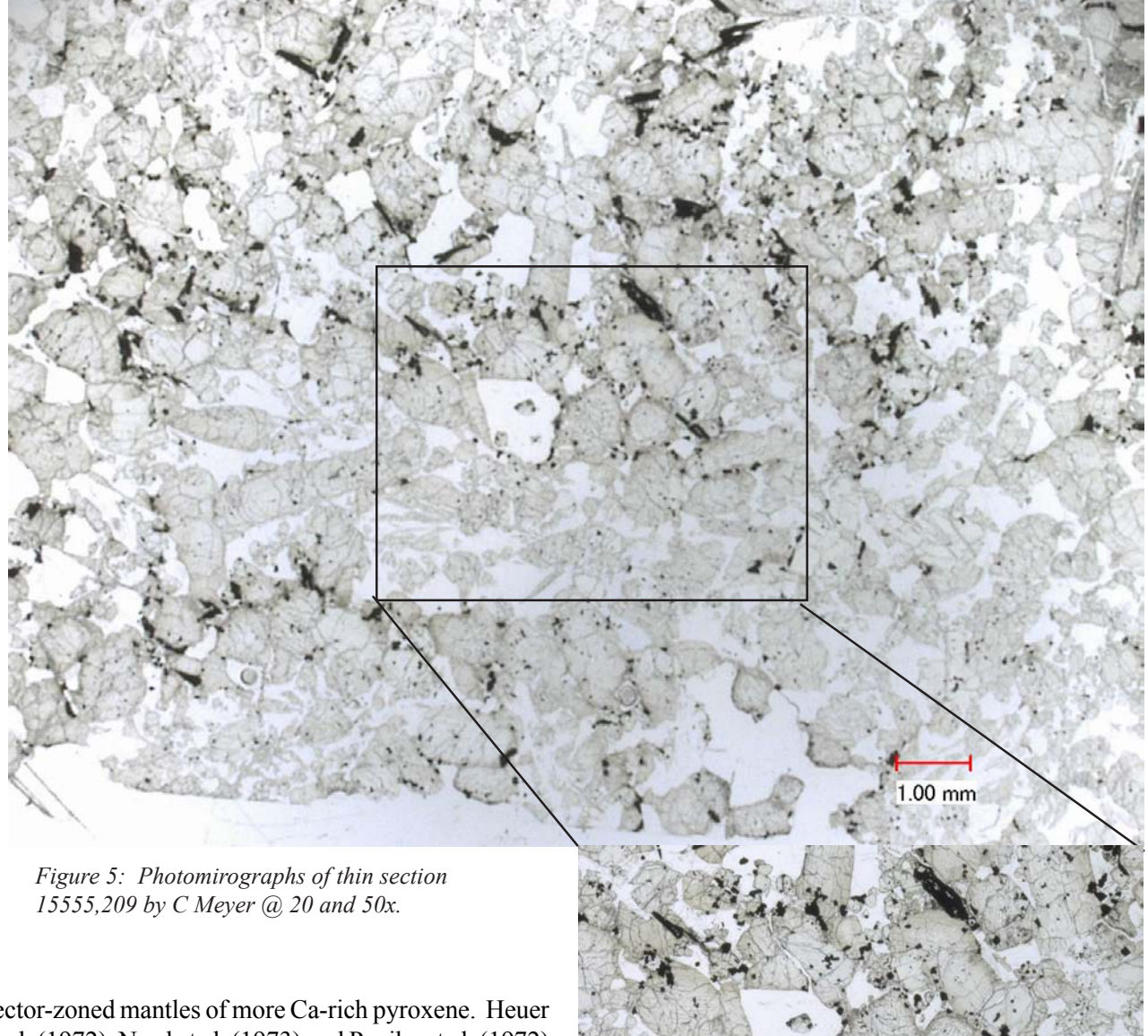

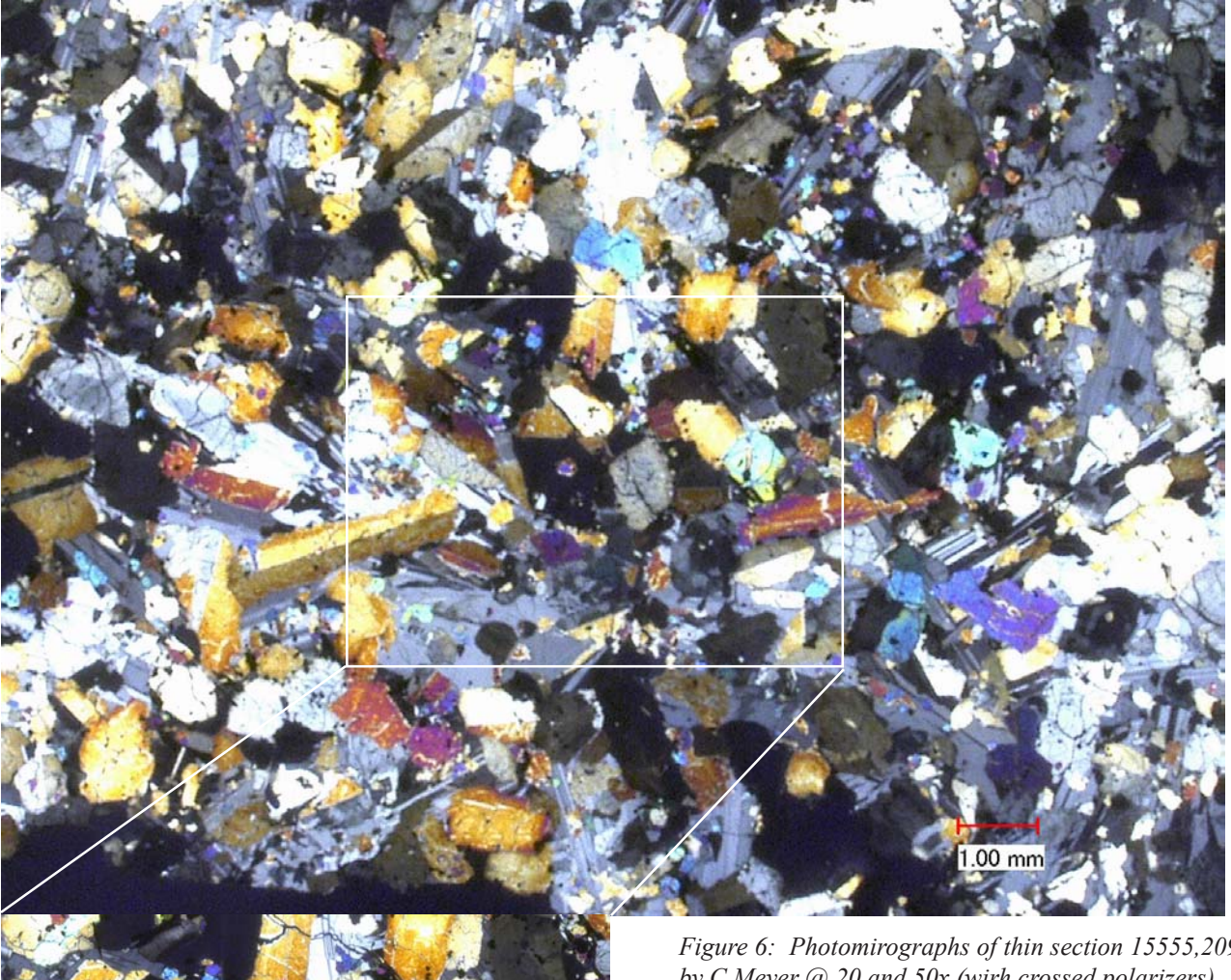

Section titled “Petrography”Lunar sample 15555 is a coarse-grained, porphryritic rock with rounded olivine phenocrysts (1 mm) and subhedral zoned pyroxene phenocrysts (0.5-2 mm) set in a matrix of poikilitic plagioclase (up to 3 mm). Interstices between plagioclase megacrysts are filled with minor opaque minerals, silica, glass and pore space. Inclusions of small euhedral chromite crystals occur in olivine and pyroxene (figure 5). Inclusions of olivine and pyroxene are found in plagioclase (figure 6). Ni-Fe metal is rare. Small vugs are about 2-4 % by volume (figure 3).

Dalton and Hollister (1974) determined the crystallization sequence of 15555 by carefully studying the mineral zoning. At 1 atmosphere, Kesson (1975) determined experimentally that olivine crystallized at 1283 deg.C, followed by spinel at 1227 deg.C, pyroxene at 1154 deg.C and plagioclase at 1138 deg.C.

Walker et al. (1977) and Taylor et al. (1977) determined the cooling rate of 15555 (5 deg.C/day) by modeling the diffusion of Fe in olivine phenocrysts, while Bianco and Taylor (1977) determined a cooling rate (at time of olivine nucleation) of 12-24 deg.C/day from the number density of olivine crystals (grains/mm2 ).

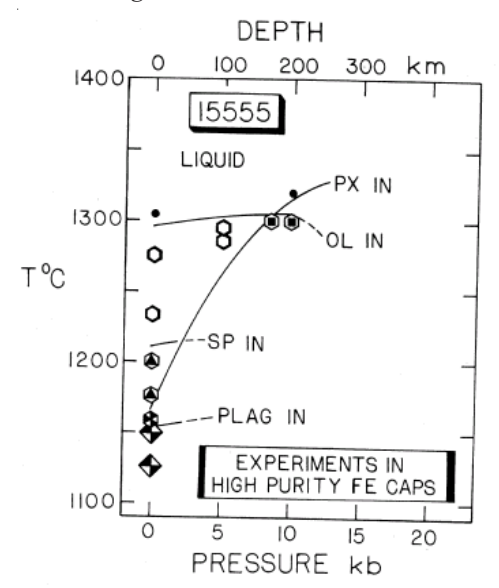

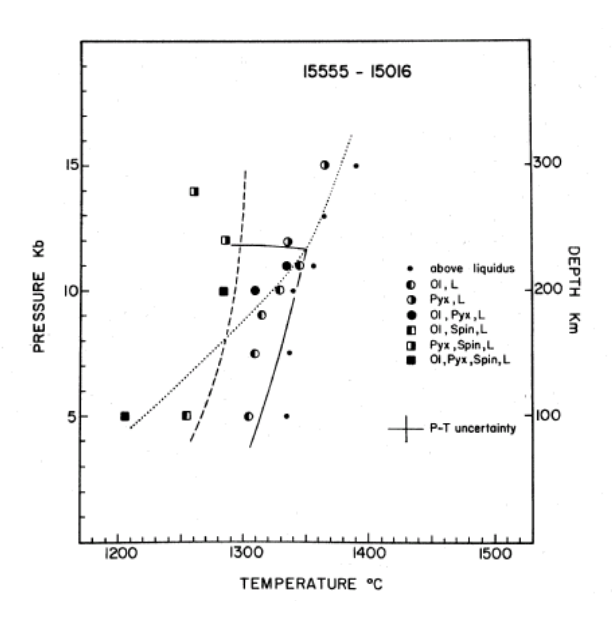

Kesson (1975) and Walker et al. (1977) performed highpressure experiments on 15555 composition to obtain

Figure 3: Closeup photo of sawn surface illustrating texture and vuggy nature of 15555,838. Sample is 3 x 5 inches. Photo # S93-045961.

the pressure-temperature relation for multiply saturated phases. In this way, they obtained estimates of the depth of origin for this composition of 240 km and 100-150 km respectively. However, it would be remarkably good fortune if a lunar basalt sample was representative of a true primary magma, because limited accumulation of olivine and/or opaques would greatly alter the liquid composition, and hence the phase diagram. Lunar basalts have very low viscosity. Never the less, the composition of 15555 (and/or 15016) was chosen for experiments, because it was highest in Mg, and thus, most likely to be the primitive end member.

Mineralogy

Section titled “Mineralogy”Olivine: Bell and Mao (1972), Brown et al. (1972), Longhi et al. (1972), Walker et al. (1977) and Taylor et al. (1977) studied the zoning in olivine phenocrysts. Dalton and Hollister (1974) reported two kinds of olivine; large (1mm), normal-zoned olivine phenocrysts with Fo and small (0.1mm) euhedral inclusions in 67-29 plagioclase with Fo49-16.

Figure 4: Photomicrograph of thin section of 15555. Scale is 2.5 mm across.

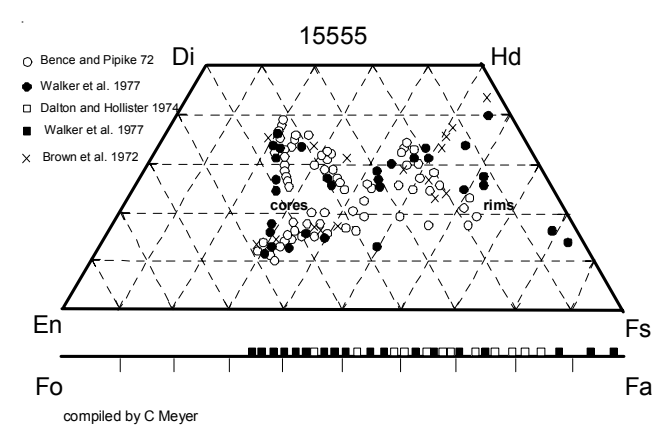

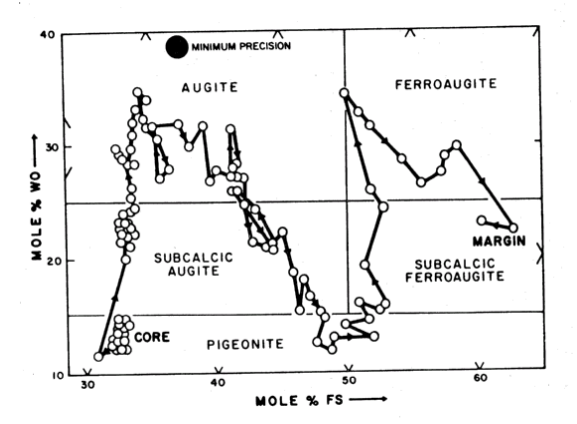

Pyroxene: Pyroxene compositions are given in plots by Brown et al. (1972), Bence and Papike (1972) and Walker et al. (1977). Coexisting, intergrown augite and pigeonite zone to a common focus and then the outer portions of pyroxene crystals zone to be extremely Fe-rich (figure 7). Mason et al. (1972) presented a traverse of the zoning in a complex pyroxene in 15555 (figure 8). Boyd (1972) found pyroxene cores had

sector-zoned mantles of more Ca-rich pyroxene. Heuer et al. (1972), Nord et al. (1973) and Papike et al. (1972) studied microscopic exsolution.

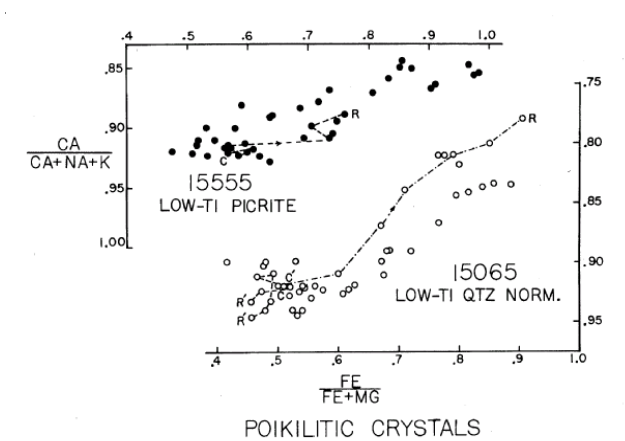

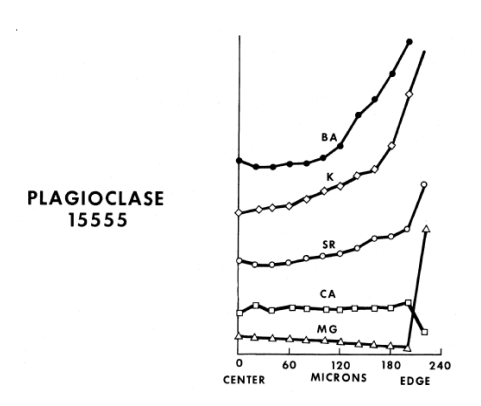

Plagioclase: The cores of large plagioclase crystals are relatively unzoned $(An_{94-91})$ but the rims approach $An_{78}$ . Longhi et al. (1976) studied the change in FeO/MgO from center to rim (figure 9) and Meyer et al. (1974) studied zoning of trace elements in 15555 (figure 10). Schnetzler et al. (1973) and Brunfelt et al. (1972) determined the trace element content of plagioclase separates.

Spinel: Dalton and Hollister (1974) found that chromite inclusions in olivine had ulvöspinel overgrowths. The spinels in 15555 have also been studied by Haggerty et al. (1972) and El Goresy et al. (1976). Some chromite has been reduced to form exsolution of ilmenite plus Fe metal.

Silica: Heuer et al. (1972) identify silica found in the mesostasis as cristobalite.

Phase Y: Brown et al. (1972) and Peckett et al. (1972) reported a Zr-Ti-Fe phase (“phase Y”) in the mesostasis which Andersen and Hinthorne (1973) were able to date by ion microprobe.

Figure 6: Photomirographs of thin section 15555,209 by C Meyer @ 20 and 50x (wirh crossed polarizers).

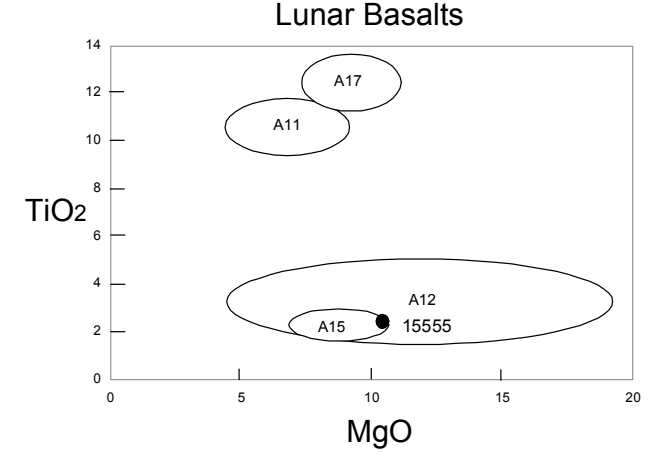

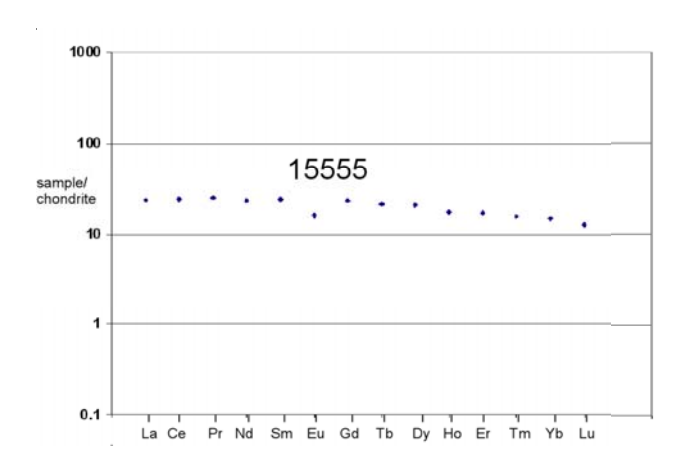

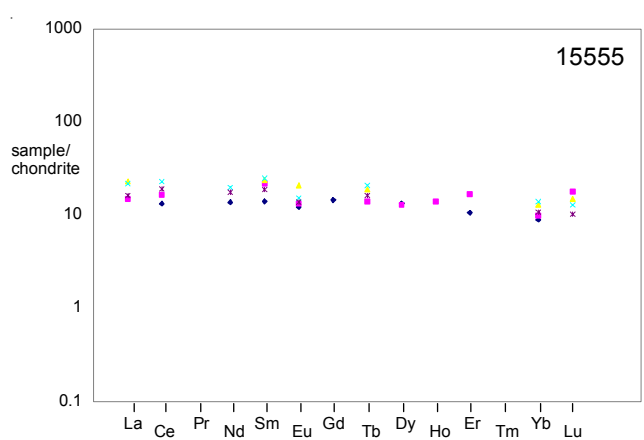

In general, 15555 is found to be typical of Apollo 15 basalts (figure 11). It is thought to be the primitive end member of the olivine-normative Apollo 15 suite (Chappell and Green 1973), and therefore suitable for high-pressure melting experiments. The rare-earthelement pattern is flat (figure 12), although agreement between labs was poor.

Chemistry

Section titled “Chemistry”The chemical composition of 15555 is given in tables 1 and 2. The lack of agreement is due to the relatively large crystal size and the small amounts distributed for analysis (see complaints lodged by Mason et al. 1972 and Rhodes and Hubbard 1973). Even Ryder and Schuraytz (2001) and Neal (2001) found significant variation in 4 gram duplicate splits.

Radiogenic age dating

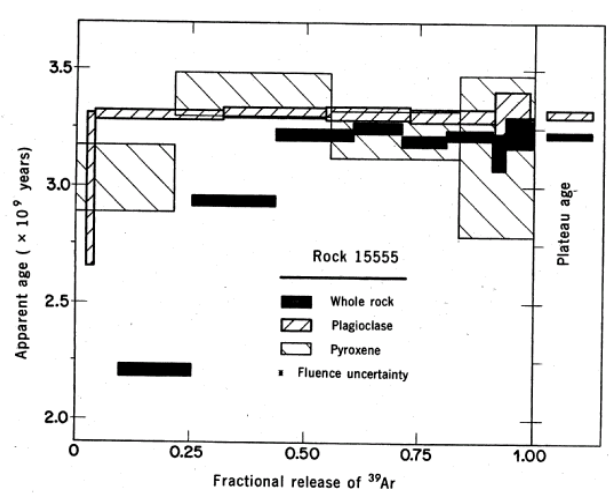

Section titled “Radiogenic age dating”15555 proved to be a good sample to resolve analytical techniques and inter-laboratory comparisons and was apparently allocated (by LAPST/CAPTEM) to each laboratory for that purpose. Argon 39/40 plateau ages were obtained by Alexander et al. (1971), Husain et al. (1971), Podosek et al. (1971) and York (1972). The most dependable ages were those obtained on plagioclase separates (figure 11).

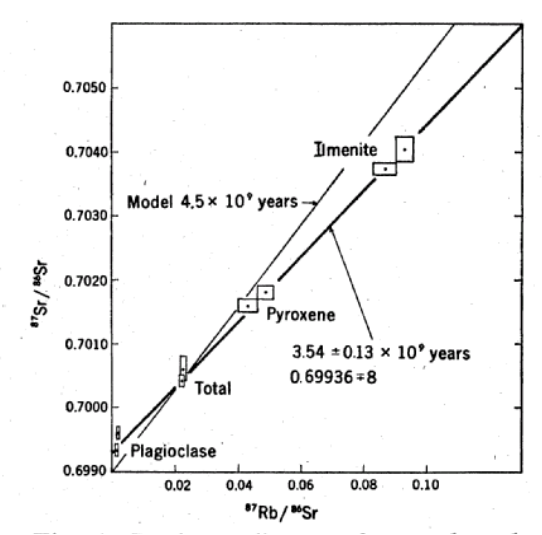

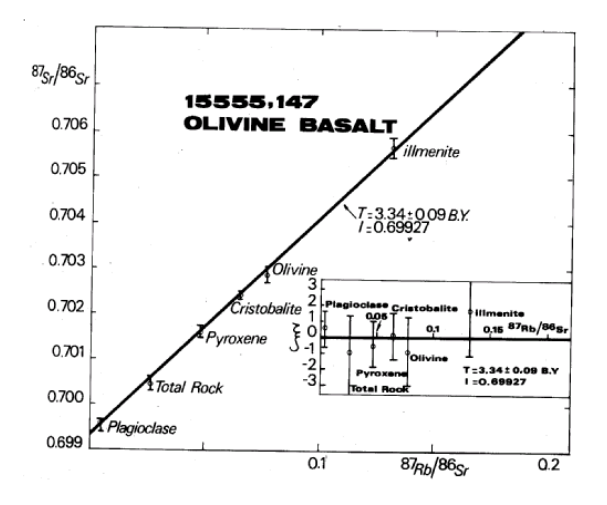

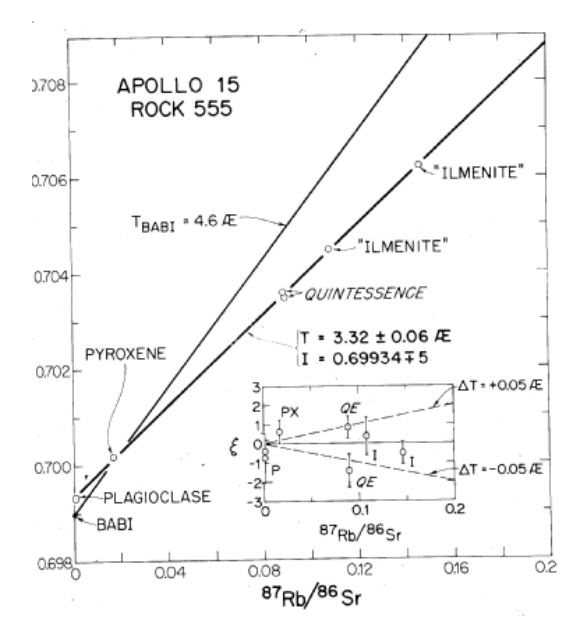

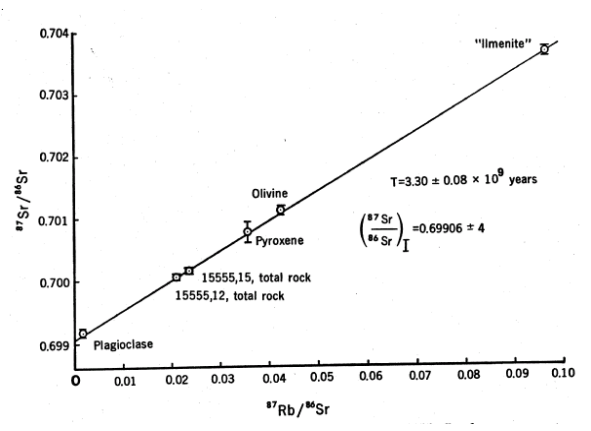

Chappell et al. (1971), Wasserburg and Papanastassiou (1971), Murthy et al. (1971), Cliff et al. (1972) and Birck et al. (1975) determined internal mineral

Figure 7: Pyroxene and olivine compositions for 15555.

Figure 8: Chemical zoning of pyroxene in 15555 from Mason et al. (1972).

isochrons by the Rb/Sr method (figures 14-17). These results are discussed in Papanastassiou and Wasserburg (1973).

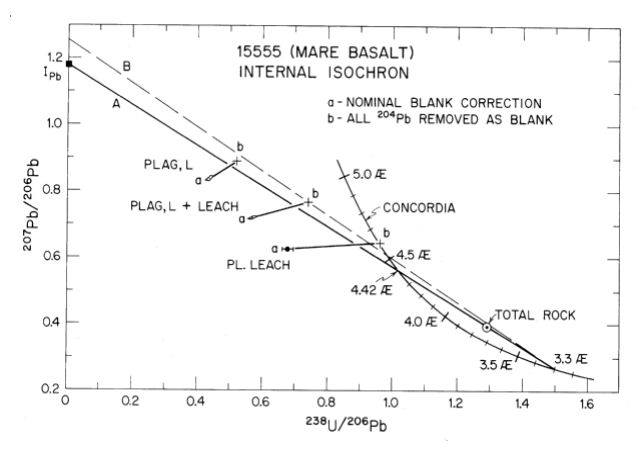

Tatsumoto et al. (1972) found that U/Pb data for 15555 lie on a discordia line from 4.65 to 3.3 b.y., while Tera and Wasserburg found that the whole rock data lie on a discordia line from 3.3 and 4.42 (magic point, see figure 18). Andersen and Hinthorne (1973) dated Urich, Y-Zr phases by ion microprobe.

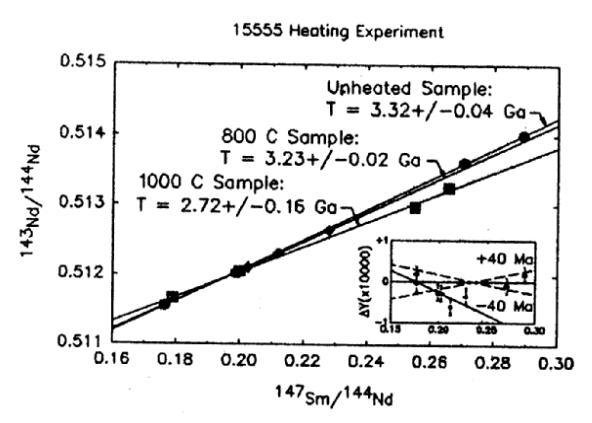

Lugmair (1975) and Unruh et al. (1984) present Sm-Nd and Lu-Hf whole rock data and Nyquist et al. (1991) have dated 15555 by Sm-Nd internal isochron (figure 17). Nyquist et al. also heated the sample to 790 deg C and 990 deg C for 170 hours to see what disturbance there was to age dating (see table).

Lee et al. (1977) reported Hf/W and 182W/184W.

It seems clear that this sample should be dated every few years, by whatever new technique, or new laboratory, that comes along, and that the data needs

Figure 9: Fe/Mg zoning in poililitic plagioclase in 15555 and 15065 (from Longhi et al. 1976).

Figure 10: Variation of minor elements in large plagioclase crystal in 15555 as determined by ion microprobe (Meyer et al. 1974).

Figure 11: Composition of 15555 comapred with other lunar basalts.

to be compared, by CAPTEM, to understand precision and accuracy that are claimed. In this way, 15555, becomes a sort of control sample for geochronology.

Figure 12a: Normalized rare-earth-element diagram for 15555 (data from Neal 2001).

Cosmogenic isotopes and exposure ages

Section titled “Cosmogenic isotopes and exposure ages”Marti and Lightner (1971) determined the cosmic ray exposure age as 81 m.y. by 81Kr . Podosek et al. (1971) and York et al. (1972) determined exposure ages of 90 m.y. and 76 m.y., respectively, by 38Ar. This age in not associated with any local crater (Arvidson et al. 1975).

The lunar orientation and history of surface exposure is not well documented for 15555 and it has not often been allocated for depth profiles of cosmic ray, solar flare radionuclide studies (however, see Fireman below). The large impact (figure 1) would have caused the rock to jump or roll! Behrmann et al. (1972) determined a track age of 34 m.y. and calculated that the erosion rate was about 1 mm per m.y. On the other hand, Poupeau et al. (1972) also determined the track density and concluded that the sample had been buried beneath the regolith. Bhandari et al. (1972) determined the track density (and suntan age).

Other Studies

Section titled “Other Studies”Lunar sample 15555 was allocated for many other studies, including physical properties, spectroscopy, thermoluminescence, isotopic analysis (C, S, Th, etc. see table). Supplemental data was collected on companion samples.

Marti and Lightner (1971), Mergue (1973) and Husain (1974) reported the content and isotopic ratios for rare gasses in 15555. Fireman et al. (1972) used measurements of 3 H (tritium), 37Ar and 39Ar from different depths in 15555 (and other Apollo samples) to determine the intensity of recent and long term solar flare activity.

Figure 12b: Normalized rare-earth-element diagram for 15555 (data from table 1a,b,c). Note the variation, but generally flat pattern.

Numerous experimental studies have been carried out on 15555 powder and/or synthetic mix (but what composition should be used?). Humphries et al. (1972), Longhi et al. (1972), Kesson (1975) and Walker et al. (1977) determined the mineral phases present at various temperatures and pressures (figures 18 and 19). If, and only if, the composition is correct and the source region contains olivine, pyroxene and plagioclase, then the depth of origin (~200 km) can be concluded from these phase diagrams.

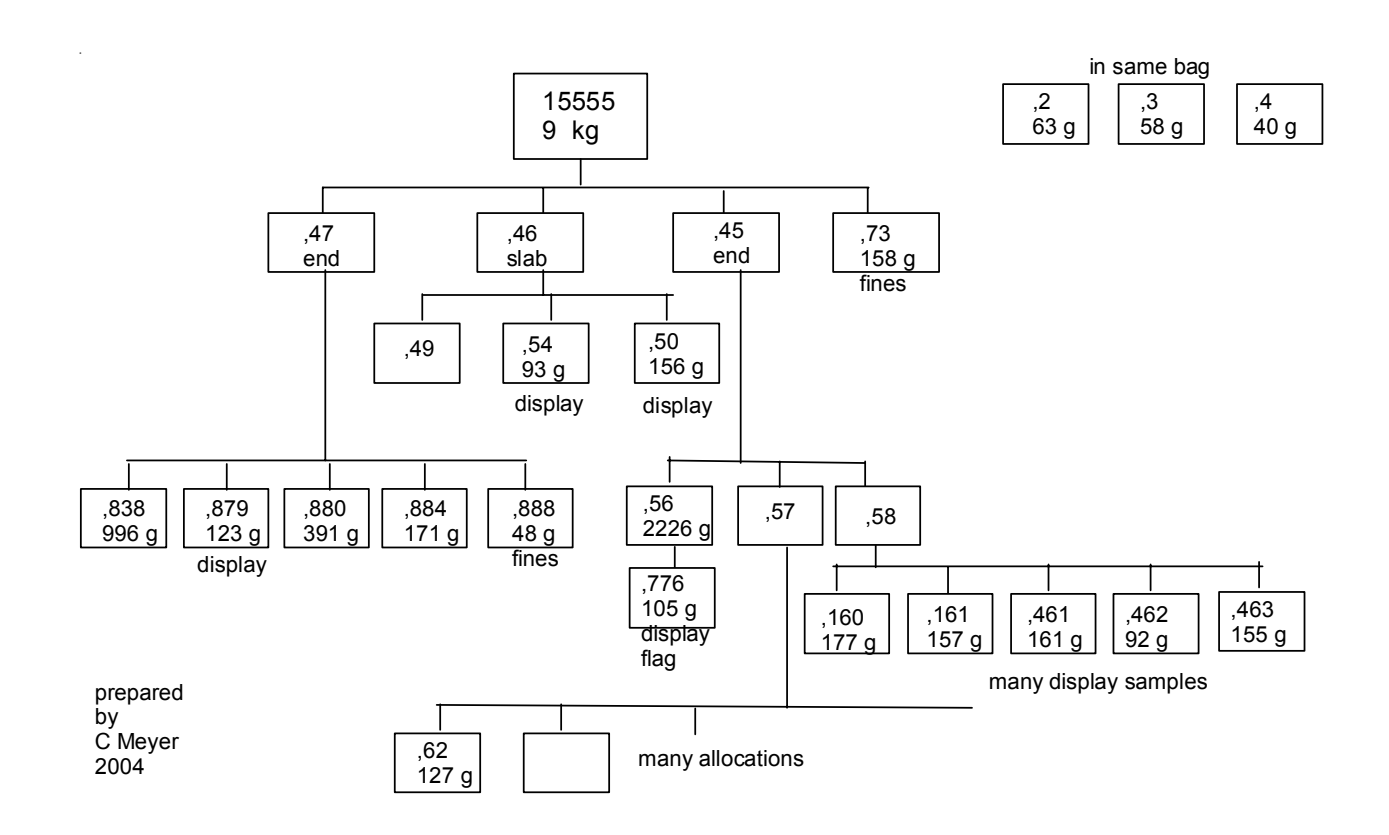

Processing

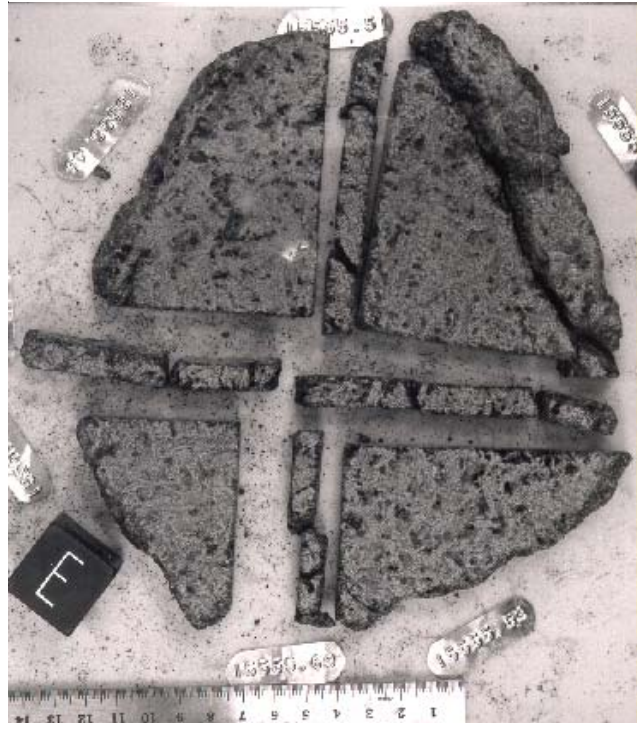

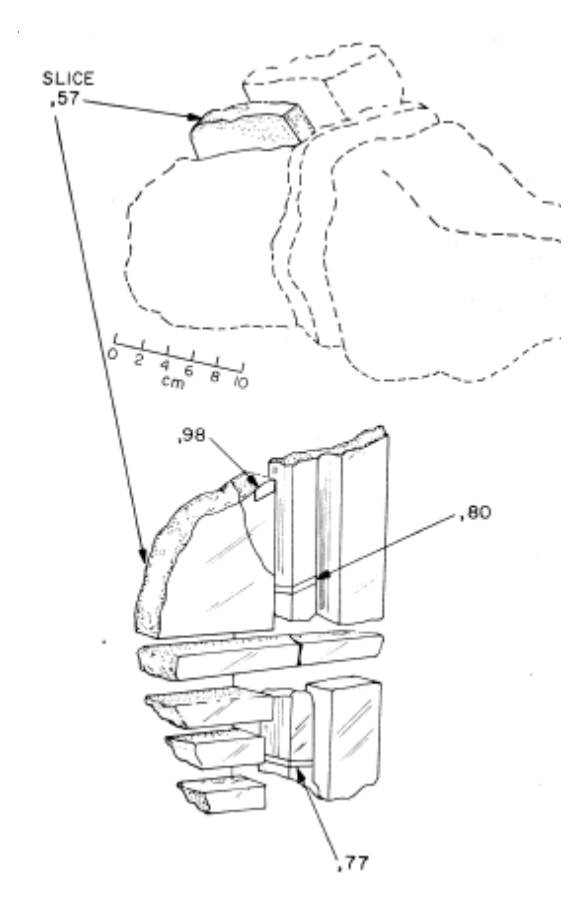

Section titled “Processing”Two slabs, cut at right angles, were made from this rock for allocations (figures 23-26). Slab ,46 is illustrated in figure 25. Slab ,57 was cut from ,48 and used for many allocations.

This large rock has been used to prepare 13 lunar sample displays, one of which is illustrated in figure 22. These are located in Edmonton, Geneva, Oakland, Yorba Linda, Denver, Washington D.C., Illinois, Kansas, Boston, Michigan, Philadelphia, Austin and Utah. Three thin sections of 15555 are also on display.

Table 1a. Chemical composition of 15555.

| weight | reference Chappell72 Schnetzler 72 Brunfelt 72 | Ganapathy 73 Rhodes 73 Cuttitta 73 | Fruchter 73 Janghorbani 73 1.5 g | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 % TiO2 Al2O3 FeO | 43.82 2.63 7.45 24.58 | (a) 45 (a) 1.6 (a) 9.37 (a) 21.18 | (c ) (c ) | (c ) 2.03 (c ) 22.13 | (d) (d) | 44.24 2.26 8.48 22.47 | (a) 45.21 (a) 1.73 (a) 10.32 (a) 20.16 | (f) | (f) 2.25 (f) 8.5 (f) 23.16 | 45.14 (d) 2.33 (d) 9.45 (d) 20.97 | 1.8 g 44.1 2.86 8.5 22.4 | (d) (d) (d) (d) | |||||

| MnO MgO | 0.32 10.96 | (a) 0.26 (a) 12.22 | (c ) | (c ) 0.3 | (d) | 0.29 11.19 | (a) 0.25 (a) 11.2 | (f) (f) | 0.26 11.77 | 0.27 10.11 | (d) (d) | ||||||

| CaO Na2O K2O | 9.22 0.24 0.04 | (a) 9.25 (a) 0.26 (a) 0.03 | (c ) | (c ) 10.35 (c ) 0.28 | (d) (d) | 9.45 0.24 0.03 | (a) 9.96 (a) 0.35 (a) 0.05 | (f) (f) | (f) 0.26 | (d) 0.39 | 0.39 | (d) | |||||

| P2O5 S % sum | 0.07 0.06 | (a) | (a) 0.07 | (c ) | 0.06 0.05 | (a) | (a) 0.05 | (f) | |||||||||

| Sc ppm | 38.4 | (d) | 40 | (f) 40 | (d) | 38 | (d) | ||||||||||

| V Cr Co Ni | 4036 | (a) 3216 | 244 (c ) 4820 61.8 90 | (d) (d) (d) (d) | 42 | 240 4516 87 (a) 96 | (f) (f) | (f) 4100 (f) 50 | (d) (d) | 3580 55 | (d) (d) | ||||||

| Cu Zn | 6.6 1.3 | (d) | (d) 0.78 | (e) | 0.13 | (f) | |||||||||||

| Ga Ge ppb | 2.9 | (d) | 8.5 | (e) | 4.6 | ||||||||||||

| As Se | <0.05 0.085 | (d) | (d) 0.156 | (e) | |||||||||||||

| Rb | 0.68 | (b) 0.445 | (b) 0.75 | (d) 0.65 | (e) 0.6 | (b) 1.1 | |||||||||||

| Sr Y | 89.7 | (b) 84.4 | (b) 84 | (d) | 92 23 | (b) 93 (a) 23 | |||||||||||

| Zr Nb | 57.3 | (b) | 76 4.3 | (a) 58 (a) 17 | |||||||||||||

| Mo | |||||||||||||||||

| Ru Rh | |||||||||||||||||

| Pd ppb Ag ppb | <7 | (d) 1 | (e) | ||||||||||||||

| Cd ppb | 2.1 | (e) | |||||||||||||||

| In ppb Sn ppb | 2 | (d) 0.55 | (e) | ||||||||||||||

| Sb ppb Te ppb | 0.067 3.4 | (e) (e) | |||||||||||||||

| Cs ppm | 0.026 | (d) 0.03 | (e) | ||||||||||||||

| Ba La | 32.2 | (b) 47 3.5 | (d) (d) | 30 | 5.4 | (d) | |||||||||||

| Ce Pr | 8.06 | (b) 10 | (d) | ||||||||||||||

| Nd | 6.26 | (b) | |||||||||||||||

| Sm Eu | 2.09 0.688 | (b) 3.2 (b) 0.75 | (d) (d) | 3.5 1.18 | (d) (d) | 1 | (d) | ||||||||||

| Gd Tb | 2.9 | (b) | 0.51 | (d) | 0.7 | (d) | 0.92 | (d) | |||||||||

| Dy | 3.27 | (b) 3.2 | (d) | ||||||||||||||

| Ho Er | 1.7 | 0.78 (b) 2.7 | (d) (d) | ||||||||||||||

| Tm Yb | 1.45 | (b) 1.64 | (d) | 4.2 | 2.1 | (d) | |||||||||||

| Lu | 0.43 | (d) | 0.37 | (d) | |||||||||||||

| Hf Ta | 2.1 0.29 | (d) (d) | 2.2 | (d) | 1.45 | (d) | |||||||||||

| W ppb Re ppb | 1200 | (d) | 0.0013 | (e) | |||||||||||||

| Os ppb | |||||||||||||||||

| Ir ppb Pt ppb | <0.1 | (d) 0.006 | (e) | ||||||||||||||

| Au ppb Th ppm | 0.48 0.3 | (d) | (d) 0.139 | (e) | |||||||||||||

| U ppm | 0.14 | (d) | |||||||||||||||

| technique (a) XRF, (b) IDMS, (c ) AA, colormetric, (d) INAA, (e) RNAA, (f) various, see paper |

Table 1b. Chemical composition of 15555.

| reference Maxwell 72 Mason 72 Unruh 84 Birck 75 | Kaplan 76 Gibson 75 | Chyi and Ehmann 73 Longhi 72 | Murthy 72 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| weight SiO2 % TiO2 Al2O3 FeO MnO | 44.22 2.36 7.54 24.24 0.29 | 0.5 g 44.75 2.07 8.67 23.4 0.3 | (f) (f) (f) (f) (f) | 45.86 2.4 8.29 23.45 | (f) (f) (f) (f) | ||||||||||

| MgO CaO Na2O K2O P2O5 S % | 11.11 9.18 0.29 0.04 0.06 0.07 | 11.48 9.14 0.24 0.05 0.05 | (f) (f) (f) (f) (f) (f) | 0.039 | (b) | 0.065 | 0.0855 (f) | 11.55 9.24 0.34 0.09 | (f) (f) (f) | (f) 0.042 (b) | |||||

| sum | |||||||||||||||

| Sc ppm V Cr Co Ni Cu Zn | 49 240 59 86 21 | 4174 | (f) (f) (f) (f) (f) (f) | 4700 | (f) | ||||||||||

| Ga Ge ppb As | |||||||||||||||

| Se Rb Sr Y | 84 25 | 0.62 91 | (b) (b) | 0.7 85.3 | (b) (b) | ||||||||||

| Zr Nb Mo Ru Rh | 140 | 130 | 124 | (d) | |||||||||||

| Pd ppb Ag ppb Cd ppb In ppb Sn ppb Sb ppb | |||||||||||||||

| Te ppb Cs ppm Ba La Ce | 48 | 41.61 (b) | |||||||||||||

| Pr Nd Sm Eu Gd | 7.518 2.52 | (b) (b) | |||||||||||||

| Tb Dy Ho Er | |||||||||||||||

| Tm Yb Lu | 4.3 | 0.255 | (b) | ||||||||||||

| Hf Ta W ppb Re ppb Os ppb Ir ppb Pt ppb Au ppb | 2 | (b) | 3.2 | 3.26 | (d) | ||||||||||

| Th ppm U ppm | technique (a) XRF, (b) IDMS, (c ) AA, colormetric, (d) INAA, (e) RNAA, (f) various, see paper |

Table 1c. Chemical composition of 15555.

| reference Ryder 2001 | duplicate | Ryder 2001 | Ryder 2001 | Chappell 73 | Nava74 | NORMALIZE Neal2001 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| weight SiO2 % TiO2 Al2O3 FeO MnO MgO CaO Na2O K2O P2O5 S % sum | 4.014 44.5 2.3 8.21 22.75 0.282 11.16 9.22 0.228 0.042 0.065 | 4.001 45 2.02 9.16 21.49 0.275 11.32 9.47 0.234 0.036 0.053 | (a) (a) (a) (a) (a) (a) (a) (a) | (a) 23 (a) 0.24 | 21.3 0.26 | 43.7 2.45 8.3 (b) 22.6 0.28 11.1 9.2 (b) 0.22 0.04 0.1 | 44.8 2.06 8.6 22 0.28 11.2 9.5 0.26 0.04 0.1 | (c ) 44.75 (c ) 2.05 (c ) 9.01 (c ) 21.68 (c ) 0.3 (c ) 11.39 (c ) 9.62 (c ) 0.27 (c ) 0.04 (c ) 0.06 0.04 | 43.82 2.63 7.45 24.58 0.32 10.96 9.22 0.24 0.04 0.07 0.06 | (a) 45 (a) 1.6 (a) 9.37 (a) 21.18 (a) 0.26 (a) 12.22 (a) 9.25 (a) 0.26 (a) 0.028 (a) 0.066 (a) | (d) (d) (d) (d) (d) (d) (d) (d) (d) (d) | ||||

| Sc ppm V | 41.4 | 39.1 | (b) | 44.2 224 | 43.8 317 | (e) (e) | |||||||||

| Cr Co Ni Cu | 4592 62 6 | 4620 67 3 | (a) | 57.4 (a) 64 | (a) 4600 4460 55.4 62 | (b) (b) | (b) 4387 | 3451 | (c ) 3968 | 4037 | (a) 3216 | (d) 4760 65.3 78.4 14.4 | 5099 66.4 81.3 13.6 | (e) (e) (e) (e) | |

| Zn Ga Ge ppb As | 2.7 | (a) | 15.5 3.74 | 16.6 3.9 | (e) (e) | ||||||||||

| Se Rb Sr Y Zr Nb Mo Ru Rh Pd ppb Ag ppb Cd ppb In ppb | 4 90 23 88 12 | 3 90 20 70 8 | (a) (a) (a) (a) | (a) 109 | 99 | (b) | 0.54 92.2 18 69 5 | 0.76 90.7 | (a) (a) (a) (a) (a) | 0.99 104.5 30.4 99.9 6.94 0.26 | 0.8 109.7 27.4 90.6 5.77 0.12 | (e) (e) (e) (e) (e) (e) | |||

| Sn ppb Sb ppb Te ppb | 30 | 20 | (e) | ||||||||||||

| Cs ppm Ba La Ce Pr | 47 5.14 13.8 | 39 3.88 11.6 | (b) (b) (b) | 0.03 56.7 5.54 14.5 2.23 | 0.01 49.9 4.73 11.8 1.79 | (e) (e) (e) (e) (e) | |||||||||

| Nd Sm Eu | 9 3.64 0.86 | 8 2.78 0.78 | (b) (b) (b) | 10.5 3.55 0.89 | 8.4 2.73 0.78 | (e) (e) (e) | |||||||||

| Gd Tb Dy Ho Er | 0.77 | 0.6 | (b) | 4.57 0.78 5.04 0.98 2.71 | 3.61 0.64 4.08 0.81 2.25 | (e) (e) (e) (e) (e) | |||||||||

| Tm Yb Lu Hf Ta W ppb Re ppb Os ppb Ir ppb | 2.28 0.31 2.8 0.4 | 1.77 0.25 2.03 0.29 | (b) (b) (b) (b) | 0.38 2.4 0.31 2.53 0.5 50 | 0.31 1.94 0.25 2.24 0.4 | (e) (e) (e) (e) (e) | |||||||||

| Pt ppb Au ppb Th ppm U ppm technique: (a) XRF, (b) INAA, (c ) fused bead, elec. Probe, (d) AA, colorimetry, (e) ICP-MS | 0.41 | 0.29 | (b) | 0.54 0.15 | 0.72 0.25 | (e) (e) |

| Rb ppm | Sr ppm | U ppm | Th ppm | K % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chappell et al. 1971 | 0.68 | 89.7 | |||

| 0.72 | 91.7 | ||||

| Murthy et al. 1971 | 0.7 | 85.32 | |||

| 0.538 | 74.11 | ||||

| Tatsumoto et al. 1972 | 0.874 | 92 | 0.0538 | ||

| 0.1264 | 0.4596 | ||||

| 0.1173 | 0.4296 | ||||

| Mark et al. 1973 | 0.675 | 0.0313 | |||

| Compston et al. 1972 | 0.63 | 89.9 |

Other Studies on 15555

Section titled “Other Studies on 15555”| topic |

|---|

Boyd 1972 pyroxene zoning Bell and Mao 1972 olivine zoning Michel-Levy and Johann 1973 petrogaphy Nord et al. 1973 HTEM , microstructure

Heuer et al. 1972 microstructure Crawford 1973 plagioclase

Czank et al. 1973 crystallographic details, plagioclase Wenk et al. 1973 crystallographic details, plagioclase Wenk and Wild 1973 crystallographic details, plagioclase Meyer et al. 1974 ion microprobe, plagioclase

Blank et al. 1982 proton microprobe, opaques

Brunfelt et al. 1973 trace element composition, plagioclase, pyroxene

Roedder and Weiblen 1972 immiscible melt inclusions

Weeks 1972 Mossbauer spectra Burns et al. 1972, 1973 microscopic spectra Huffman et al. 1972, 1974, 1975 Mossbauer spectra Simmons et al. 1975 microcracks Cukierman et al. 1973 recrystallization Mark et al. 1973 age dating

Husain 1974 age dating Friedman et al 1972 Pyrolysis, H, C isotopes

Eisenstraut et al. 1972 GC

Gibson et al 1975 Combustion

Kaplan et al. 1976 Combustion, S, C isotopes DesMarais et al. 1978 Combustion, C isotopes Allen et al 1973 INAA, Pb etc.

Rosholt 1974 Th isotopes Fleischer et al. 1973 tracks

Megrue 1973 laser probe, rare gases Fireman et al. 1972 solar wind rare gas Collinson et al. 1972, 1973 magnetic data Pearce et al. 1972, 1973 magnetic data Dunn and Fuller 1972 magnetic data Hargraves et al 1972 magnetic data Nagata et al. 1972, 1973 magnetic data Schwerer and Nagata 1976 magnetic data

Chung and Westphal 1973 dielectric data Schwerer et al. 1973, 1974 electrical conductivity Schwerer et al. 1973 Mossbaurer spectra Tittmann et al. 1972 seismic wave velocity

Warren et al 1973 seismic wave velocity, pressure Chung 1973 seismic wave velocity, pressure

Hemingway et al. 1973 specific heat Adams and McCord 1972 reflectance spectra

Charrette and Adams 1975 reflectance spectra Brito et al. 1973 thermoluminescence studies

Cukiermann et al. 1973 viscosity Cukiermann and Uhlmann 1974 viscosity

Figure 13: Argon 39/40 plateau ages for plagioclase and whole rock 15555 from Podosek et al. (1972).

Figure 15: Rb/Sr internal mineral isochron for 15555 (from Chappell et al. 1971).

Figure 17: Rb/Sr internal mineral isochron for 15555 (from Birck et al. 1975).

Figure 14: Rb/Sr internal mineral isochron for 15555 from Wasserburg and Papanastassiou (1971).

Figure 16: Rb/Sr internal mineral isochron for 15555 (from Murthy et al. 1971).

| List of NASA photo #s for 15555 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S71-43390-43394 | color, dusty | ||||||||

| S71-43952-43954 | dust free | ||||||||

| S71-51781-51795 | TS | ||||||||

| S71-52201 | TS | ||||||||

| S71-52213 | TS | ||||||||

| S71-57110 | after slab cut, B&W | ||||||||

| S71-57987 | exploded parts, slab | ||||||||

| S74-23072 | TS | ||||||||

| S74-31406-31413 | ,461 - ,463 | ||||||||

| S75-33416-33421 | ,56 | ||||||||

| S79-27098-27100 | set of thin sections | ||||||||

| S85-29591-29600 | ,791 - ,463 | ||||||||

| S90-37023 | ,160 | ||||||||

| S93-45953-45962 | ,838 | ||||||||

| S96-09087 | ,880 |

S97-16866 ,880

Figure 18: U-Pb data for leaches and “whole rock” splits. Line is drawn thru whole rock data and intersection at 3.3 (the age determined by Rb-Sr) (from Tera and Wasserburg 1971).

Figure 19: Sm-Nd internal mineral isochron for 15555 from Nyquist et al. (1991). Linear arrays are also determined for heat treated samples, but with lower ages!

Figure 20: Experimental phase diagram for 15555 from Walker et al. (1977).

| Summary of Age Data for 15555 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rb/Sr | Ar/Ar | U/Pb | Pb/Pb | Sm/Nd | |

| Chappell et al. 1971 | 3.54 ± 0.13 b.y. | ||||

| Wasserburg, Pap 1971 | 3.32 ± 0.06 | ||||

| Alexander et al. 1971 | 3.33 ± 0.05 | ||||

| Husain et al. 1971 | 3.28 ± 0.06 | ||||

| Murthy et al. 1971 | 3.3 ± 0.08 | ||||

| Podosek et al. 1971 | 3.22 ± 0.03 | ||||

| plagioclase | 3.31 ± 0.03 | ||||

| York et al. 1972 | 3.31 ± 0.05 | ||||

| Cliff et al. 1972 | 3.34 | ||||

| Papanastassiou, W 1973 | 3.32 ± 0.04 | ||||

| Birck et al. 1975 | 3.34 ± 0.09 | ||||

| Tatsumoto et al. 1972 | 3.3 (and 4.65) | ||||

| Tera and Wasserburg 1974 | 3.3 (and 4.42) | ||||

| Andersen and Hinthorne 1973 | 3.36 ± 0.06 | ||||

| 3.46 ± 0.09 | |||||

| Nyquist et al. (1991) | 3.32 ± 0.04 | ||||

| (heated) | 3.23 ± 0.02 |

Caution: These ages have not been updated using new decay constants.

Figure 21: Experimental phase diagram for 15555 by Kesson (1975).

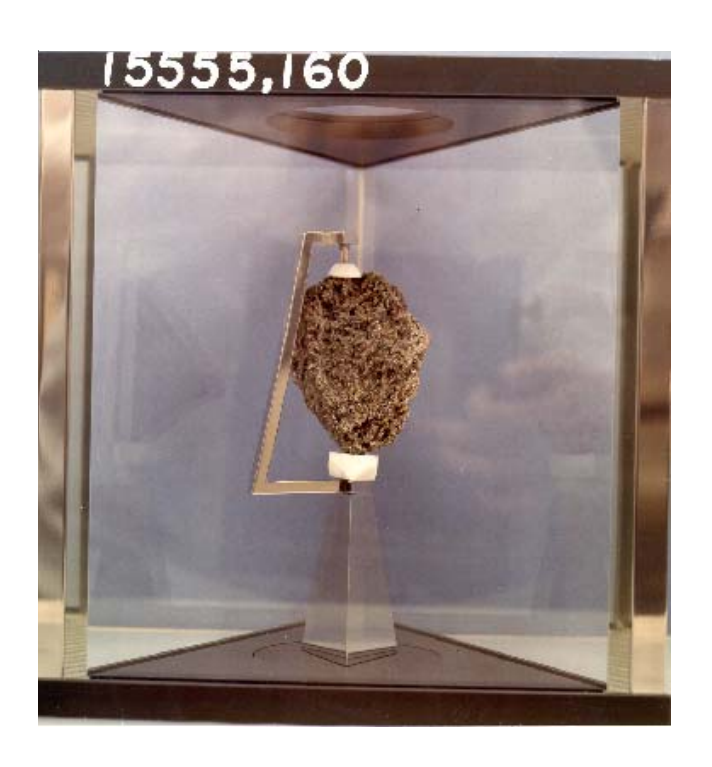

Figure 22: Display case with 15555,160. Case is made from optical glass and filled with dry nitrogen.

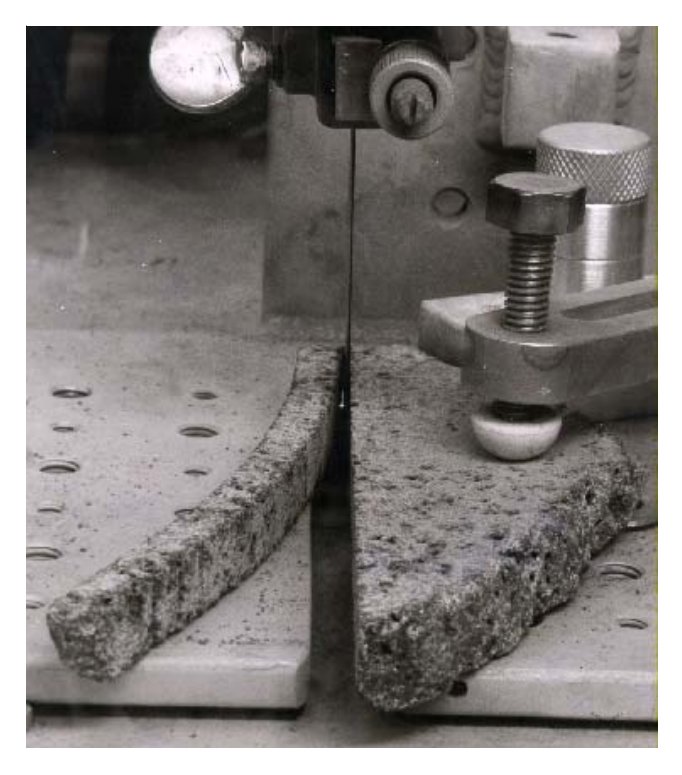

Figure 23: First saw cuts of 15555. Photo number S71-57110. Cube is 1 inch.

Figure 24: Sawing slab. Photo # S71-57094. Figure 25: Parts diagram for slab 15555,46. Photo # S71-57987. Cube is 1 inch.

Figure 26: Location of samples studied by Fireman et al. (1972) in second slab (,57) cut from 15555,45.

References for 15555

Section titled “References for 15555”Alexander E.C., Davis P.K. and Lewis R.S. (1972) Rubidium-strontium and potassium-argon age of lunar sample 15555. Science 175, 417-419.

Andersen C.A. and Hinthorne J.R. (1973) 207Pb/206Pb ages and REE abundances in returned lunar materials by ion microprobe mass analysis (abs). Lunar Sci. IV, 37-42. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Arvidson R., Crozaz G., Drozd R.J., Hohenberg C.M. and Morgan C.J. (1975) Cosmic ray exposure ages of features and events at the Apollo landing sites. The Moon 13, 259 276.

Behrmann C., Crozaz G., Drozd R., Hohenberg C.M., Ralston C., Walker R.M. and Yuhas D. (1972) Rare gas and particle track studies of Apollo 15 samples: Hadley Rille and special studies of Apollo 15 samples. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples, 26-28. Lunar Sci. Institute, Houston.

Bell P.M. and Mao H.K. (1972a) Zoned olivine crystals in an Apollo 15 lunar rock. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples, 26-28. Lunar Sci. Institute, Houston.

Bence A.E. and Papike J.J. (1972) Pyroxenes as recorders of lunar basalt petrogenesis: Chemical trends due to crystalliquid interaction. Proc. 3rd Lunar Sci. Conf. 431-469.

Bhandari N., Goswami J.N., Gupta S.K., Lal D., Tamhane A.S. and Venkatavaradan V.S. (1972) Collision controlled radiation history of the lunar regolith. Proc. 3rd Lunar Sci. Conf. 2811-2829.

Birck J.L., Fourcade S. and Allegre C.J. (1975) 87Rb/86Sr age of rocks from the Apollo 15 landing site and significance of internal isochron. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 26, 29-35.

Bianco A.S. and Taylor L.A. (1977) Applications of dynamic crystallation studies: lunar olivine-normative basalts. Proc. 8th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1583-1610.

Boyd F.R. (1972) Zoned pyroxenes in lunar rock 15555. Carnegie Inst. Wash. Yearbook 71, 459-463.

Brown G.M., Emeleus C.H., Holland G.J., Peckett A. and Phillips R. (1972) Mineral-chemical variations in Apollo 14 and Apollo 15 basalts and granitic fractions. Proc. 3rd Lunar Sci. Conf. 141-157.

Brunfelt A.O., Heier K.S., Nilssen B., Steiennes E. and Sundvoll B. (1972) Elemental composition of Apollo 15 samples. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples (Chamberlain J.W. and Watkins C., eds.), 195-197. Lunar Science Institute, Houston.

Chappell B.W., Compston W., Green D.H. and Ware N.G. (1972) Chemistry, geochronology and petrogenesis of lunar sample 15555. Science 175, 415-416

Chappell B.W. and Green D.H. (1973) Chemical compositions and petrogenetic relationships in Apollo 15 mare basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 18, 237-246.

Cliff R.A., Lee-Hu C. and Wetherill G.W. (1972) K, Rb and Sr measurements in Apollo 14 and 15 material (abs). Lunar Science III, 146-147.

Dalton J. and Hollister L.S. (1974) Spinel-silicate cocrystallization relations in sample 15555. Proc. 5th Lunar Sci. Conf. 421-429.

El Goresy A., Prinz M. and Ramdohr P. (1976a) Zoning in spinels as an indicator of the crystallization histories of mare basalts. Proc. 7th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1261-1279.

Fireman E.L., D’Amico J., DeFelice J. and Spannagel G. (1972) Radioactivities in returned lunar materials. Proc. 3rd Lunar Sci. Conf. 1747-1762.

Haggerty S.E. (1972) Chemical characteristics of spinels in some Apollo 15 basalts. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples 92-97. Lunar Science Institute.

Haggerty S.E. (1972) Solid solution, subsolidus reduction and compositional characteristics of spinels in some Apollo 15 basalts. Meteoritics 7, 353-370.

Heuer A.H., Nord G.L., Radcliffe S.V., Fischer R.M., Lally J.S., Christie J.M. and Griggs D.T. (1972) High voltage electron peterographic study of Apollo 15 rocks. In Apollo 15 Lunar Samples. 98-102.

Husain L., Schaeffer O.A., Funkhauser J. and Sutter J. (1972) The ages of lunar materials from Fra Mauro, Hadley Rille and Spur Crater. Proc. 3rd Lunar Science Conf. 1557-1567.

Husain L. (1972) 40Ar-39Ar and cosmic ray exposure ages of the Apollo 15 crystalline rocks, breccias and glasses (abs). In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples. 374-375. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Husain L. (1974) 40Ar-39Ar chronology and cosmic ray exposure ages of the Apollo 15 samples. J. Geophys. Res. 79, 2588-2606.

Humphries D.J., Biggar G.M and O’Hara M.J. (1972) Phase equilibria and origin of Apollo 15 basalts etc. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples. 103-107. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Kesson S.E. (1975a) Mare basalt petrogenesis. In Papers presented to the Conference on Origins of Mare Basalts and their Implications for Lunar Evolution (Lunar Science Institute, Houston), 81-85. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Kesson S.E. (1975b) Mare basalts: melting experiments and petrogenetic interpretations. Proc. 6th Lunar Sci. Conf. 921 944.

Lee D-C., Halliday A.N., Snyder G.A. and Taylor L.A. (1997) Age and origin of the Moon. Science 278, 1098-1103.

Longhi J., Walker D., Stolper E.N., Grove T.L. and Hays J.F. (1972) Petrology of mare/rille basalts 15555 and 15065. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples, 131-134.

Longhi J., Walker D. and Hays J.F. (1976) Fe and Mg in plagioclase. Proc. 7th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1281-1300.

Lugmair G.W. (1975) Sm-Nd systematics of some Apollo 17 basalts. In Papers presented to the Conference on Origins of Mare Basalts and their Implications for Lunar Evolution (Lunar Science Institute, Houston), 107-110.

Mason B., Jarosewich E., Melson W.G. and Thompson G. (1972) Mineralogy, petrology, and chemical composition 15476, 15535, 15555, and 15556. Proc. 3rd Lunar Sci. Conf. 785-796.

Marti K. and Lightner B.D. (1972) Rare gas record in the largest Apollo 15 rock. Science 175, 421-422.

Mergue G.H. (1973b) Distribution of gases within Apollo 15 samples: Implications for the incorporation of gases within solid bodies of the Solar System. J. Geophys. Res. 78, 4875-4883.

Meyer C., Anderson D.H. and Bradley J.G. (1974) Ion microprobe mass analysis of plagioclase from “non-mare” lunar samples. Proc. 5th Lunar Sci. Conf. 685-706.

Murthy V.R., Evensen N.M., Jahn B.-M. and Coscio M.R. (1972) Apollo 14 and 15 samples: Rb-Sr ages, trace elements, and lunar evolution. Proc. 3rd Lunar Sci. Conf. 1503-1514.

Neal C.R. (2001) Interior of the moon: The presence of garnet in the primitive deep lunar mantle. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 27865-27885.

Nord G.L., Lally J.S., Heuer A.H., Christie J.M., Radcliffe S.V., Griggs D.T. and Fisher R.M. (1973) Petrologic study of igneous and metaigneous rocks from Apollo 15 and 16 using high voltage transmission electron microscopy. Proc. 4th Lunar Sci. Conf. 953-970.

Nyquist L.E., Bogard D.D., Garrison D.H., Bansal B.M., Wiesmann H. and Shih C-Y. (1991a) Thermal resetting of radiometric ages. I: Experimental Investigations (abs). Lunar Planet. Sci. XXII, 985-986. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Nyquist L.E., Bogard D.D., Garrison D.H., Bansal B.M., Wiesmann H. and Shih C-Y. (1991b) Thermal resetting of radiometric ages. II: Modeling and applications (abs). Lunar Planet. Sci. XXII, 987-988. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston

Papanastassiou D.A. and Wasserburg G.J. (1973) Rb-Sr ages and initial strontium in basalts from Apollo 15. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 17, 324-337.

Papike J.J., Bence A.E. and Ward M.A. (1972) Subsolidus relations of pyroxenes from Apollo 15 basalts. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples. 144-147. Lunar Sci. Institute, Houston.

Papike J.J., Hodges F.N., Bence A.E., Cameron M. and Rhodes J.M. (1976) Mare basalts: Crystal chemistry, mineralogy and petrology. Rev. Geophys. Space Phys. 14, 475-540.

Peckett A., Phillips R. and Brown G.M. (1972) New zirconium-rich minerals from Apollo 14 and 15 lunar rocks. of lunar samples 15085, 15256, 15271, 15471, 15475, Nature 236, 215-217.

Podosek F.A., Huneke J.C. and Wasserburg G.J. (1972) Gas retention and cosmic ray exposure ages of lunar rock 15555. Science, 175, 423-425.

Poupeau G., Pellas P., Lorin J.C., Chetrit G.C. and Berdot J.L. (1972) Track analysis of rocks 15058, 15555, 15641 and 14307. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples. 385-387. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Rhodes J.M. and Hubbard N.J. (1973) Chemistry. Classification, and petrogenesis of Apollo 15 mare basalts. Proc. 4th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1127-1148.

Ryder G. and Schuraytz B.C. (2001) Chemical variations of the large Apollo 15 olivine-normative mare basalt rock samples. J. Geophys. Res. 106, E1, 1435-1451.

Schnetzler C.C., Philpotts J.A., Nava D.F., Schuhmann S. and Thomas H.H. (1972) Geochemistry of Apollo 15 basalt 15555 and soil 15531. Science 175, 426-428.

Tatsumoto M., Hedge C.E., Knight R.J., Unruh D.M. and Doe Bruce R. (1972b) U-Th-Pb, Rb-Sr and K measurements on some Apollo 15 and Apollo 16 samples. In The Apollo 15 Lunar Samples (Chamberlain and Watkins eds) 391 395. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Taylor L.A., Onorato PIK and Uhlmann D.R. (1977) Cooling rate estimations based on kinetic modeling of Fe-Mg diffusion in olivine. Proc. 8th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1581-1592.

Tera F. and Wasserburg G.J. (1974) U-Th-Pb systematics on lunar rock: and inferences about lunar evolution and the age of the Moon. Proc. 5th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1571-1599.

Unruh D.M., Stille P., Patchett P.J. and Tatsumoto M. (1984) Lu-Hf and Sm-Nd evolution in lunar mare basalts. Proc. 14th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. in J. Geophys. Res. 88, B459 B477.

Wasserburg G.J. and Papanastassiou D.A. (1971) Age of an Apollo 15 mare basalt: lunar crust and mantle evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 13, 97-104.

Walker D., Longhi J., Lasaga A.C., Stolper E.M., Grove T.L. and Hays J.F. (1977) Slowly cooled microgabbros 15555 and 15056. Proc. 8th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1521-1547.

York D., Kenyon W.J. and Doyle R.J. (1972) 40Ar-39Ar ages of Apollo 14 anf 15 samples. Proc. 3rd Lunar Sci. Conf. 1613-1622.