Sample 69935

Breccia 127.6 grams

Section titled “Breccia 127.6 grams”

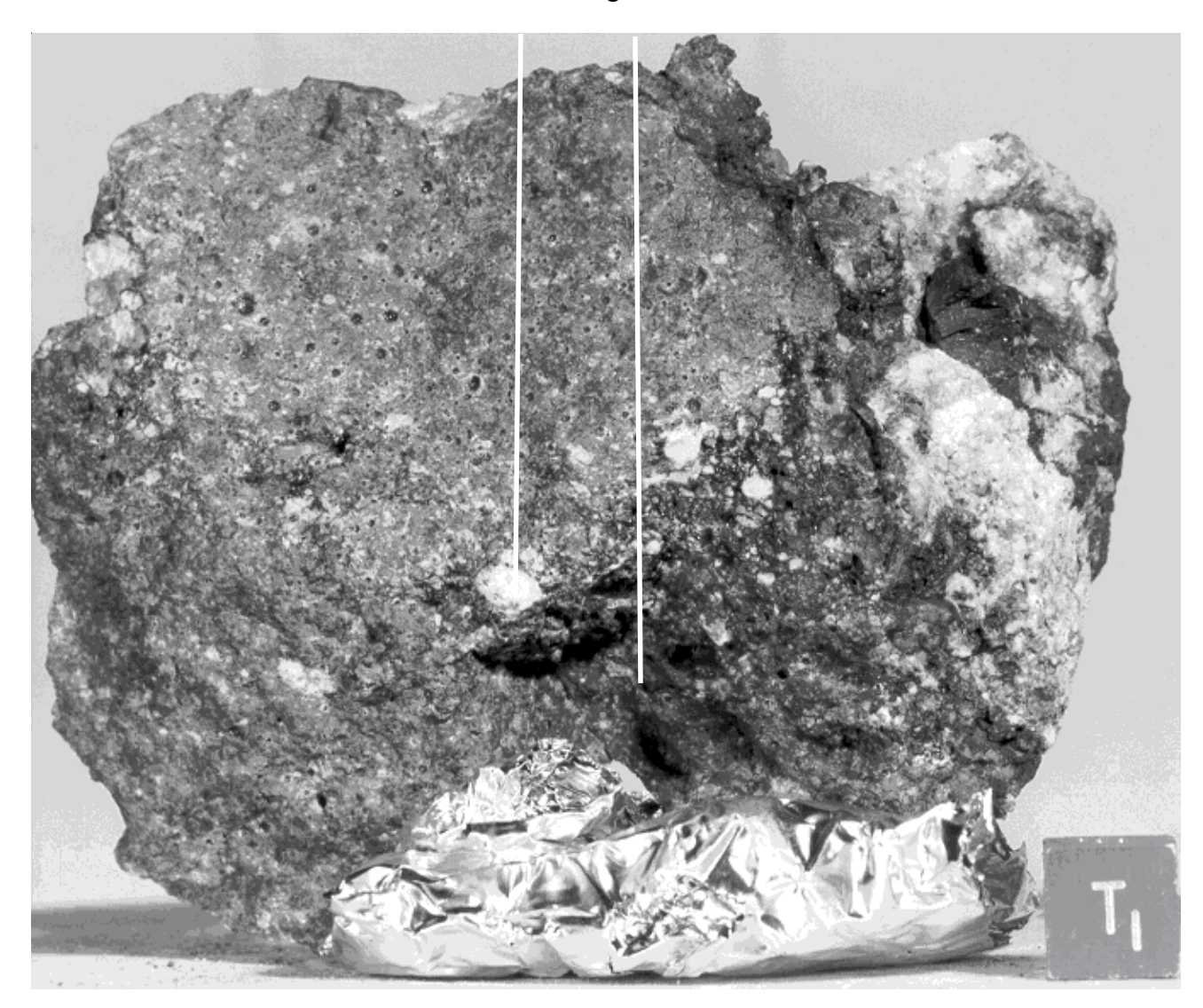

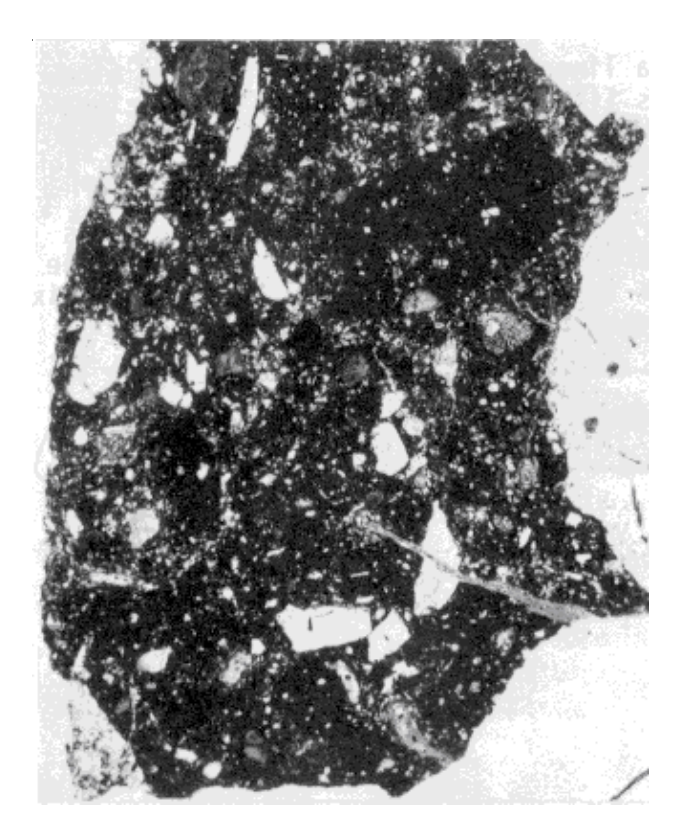

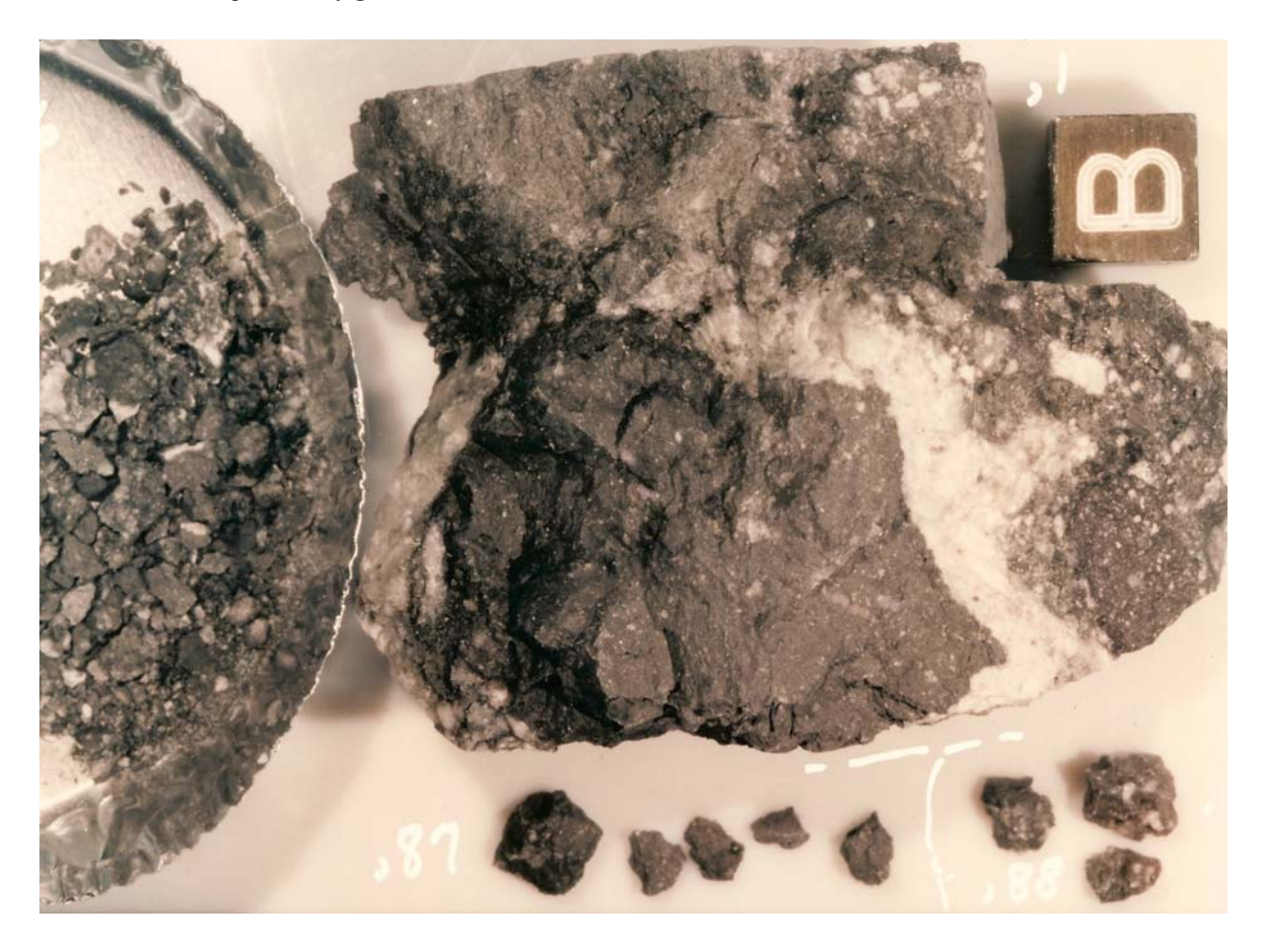

Figure 1: Photo of top exposed surface (T1) of 69935 showing abundant distribution of micrometeorite craters on polymict substrate. NASA S72-44455. Cube is 1 cm. White lines are approximate location of saw cuts - see figure 11.

Introduction

Section titled “Introduction”69935 was chipped from the top of a 0.5 meter boulder at station 9, Apollo 16 – see picture in 69955. The top surface is covered with micrometeorite pits (figures 1 and 2), and this rock has been used to understand the flux of micrometeorites and erosion of boulder surface over the past 2 m.y. However, the exposure age obtained for the top of this boulder is not consistent with that of the sample from the bottom (69955), nor the data from track studies. No fillet has developed

around the boulder so it is thought to have been recently set out on top of the regolith (Sutton 1981).

The case for this to represent the age of the cratering event at South Ray crater is made by Eugster (1999).

Petrography

Section titled “Petrography”69935 is an apparently a polymict breccia that is texturally inhomogeneous (Ryder and Norman 1980). It contains a rather large white clast (figure 1, 3, 4). The matrix of 69935 appears to be that of a soil breccia

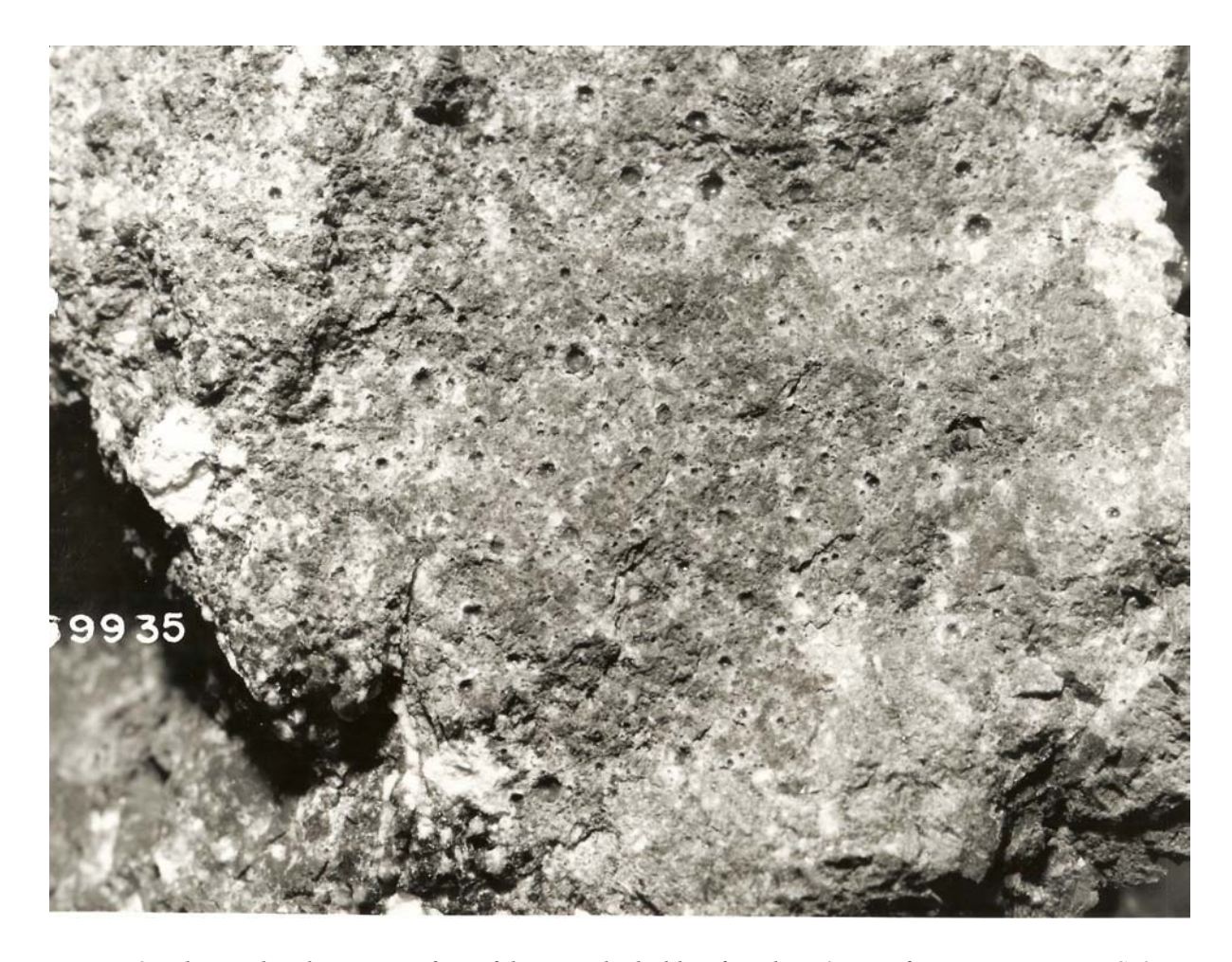

Figure 2: This is what the outer surface of the moon looks like after about 2 m.y. of expsoure to space. S72- 44540. It is, of course, somewhat abraded due to handling. Field of view is 4 cm.

Transcript

Section titled “Transcript”The astronauts were doing several things at once, but the comments pertaining to sampling the small boulder are as follow:

LMP We can turn this rock over. If you want us to get that sample in, we need an extension.

CC All right.

LMP John, you want to start sampling while I do that. Can you turn that over by yourself/

CDR Well, I’m going to give it a go.

LMP Getting a sample off of it, John?

CDR Yeah (69935). The top of that rock is hard breccia, and I’m just going to throw it under your seat, Charlie.

LMP He did it, Houston! He did it.

CC So you can not only sneak up on them, you can flip them over, huh?

CDR Yeah. That’s a biggie. Man. It looks like it been sitting there for quite a while. Look at that soil underneath.

CC Right. A chip off of the bottom and the soil will probably do it.

CDR A chip off the bottom.

LMP I see a place where we can get a chip off the bottom. The bottom is glass covered, Houston. Yeah, white glass.

CRD No, the black stuff is the glass. That other is the crystal. That’s a crystalline rock. (69955)

CC Now you found a real rock.

LMP Aha! Look at that piece here, let me get it John, Back up. I’ll go get it. There it is right there.

CRD Can you pick it up with your shovel?

LMP I don’t want to get it too dirty. Okay, we got you about a 4 cm chip. That’s not glass, John. Those are crystals. Those are big crystals. At least 5 mm, with a bluish cast to them.

CDR That’s going in bag 380, Houston. It looks to me like it’s a shocked rock with a lot of - and this is a guess – a lot of black glass in the fractures.

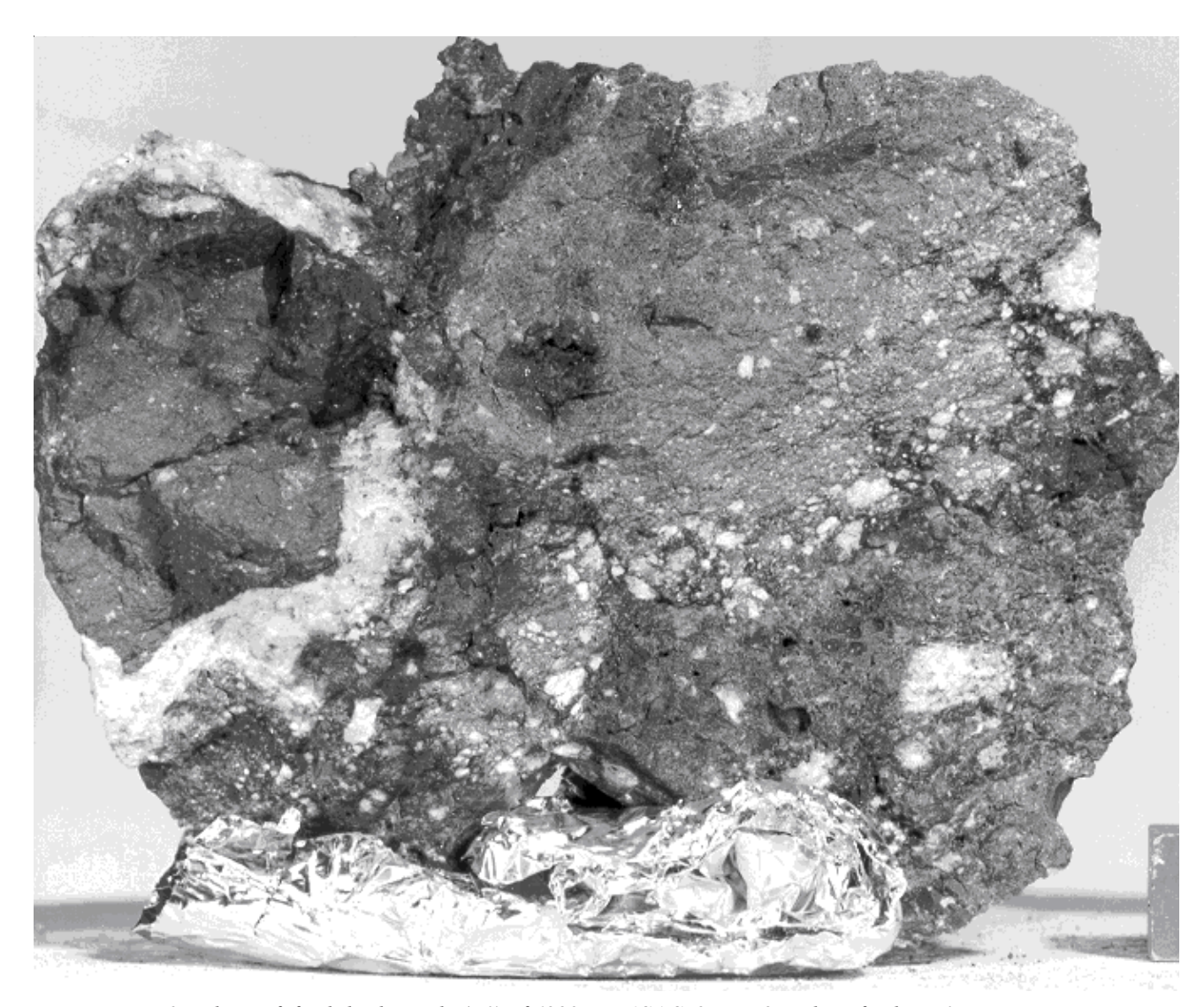

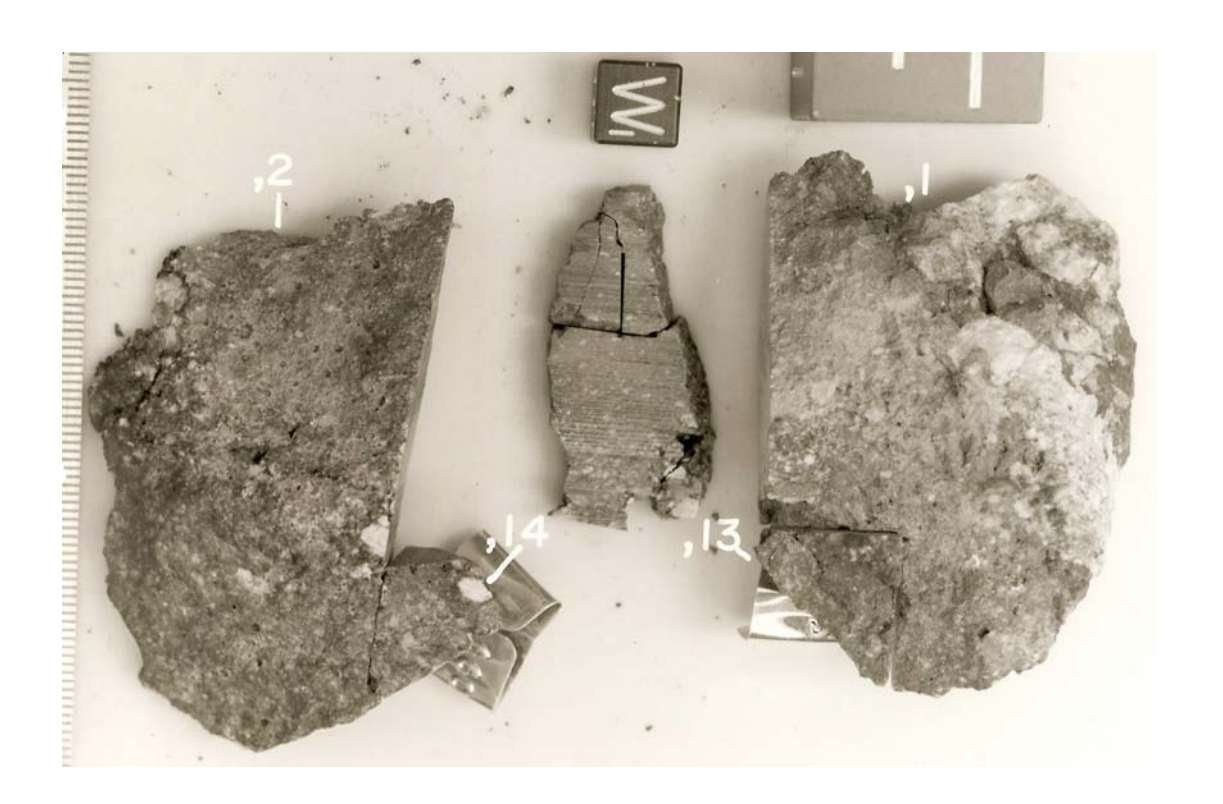

Figure 3: Photo of fresh-broken side (B1) of 69935. NASA S72-44459. Edge of cube is 1 cm. Note the white clast. Ignore the Al-foil.

(figures 3 and 5). However, the mineralogy of this sample has generally not been documented by petrologists. There are no mineral analyses.

Metal grains in 69935 are rusted (Misra and Taylor 1975).

Significant Clast

Section titled “Significant Clast”Anorthosite Clast:

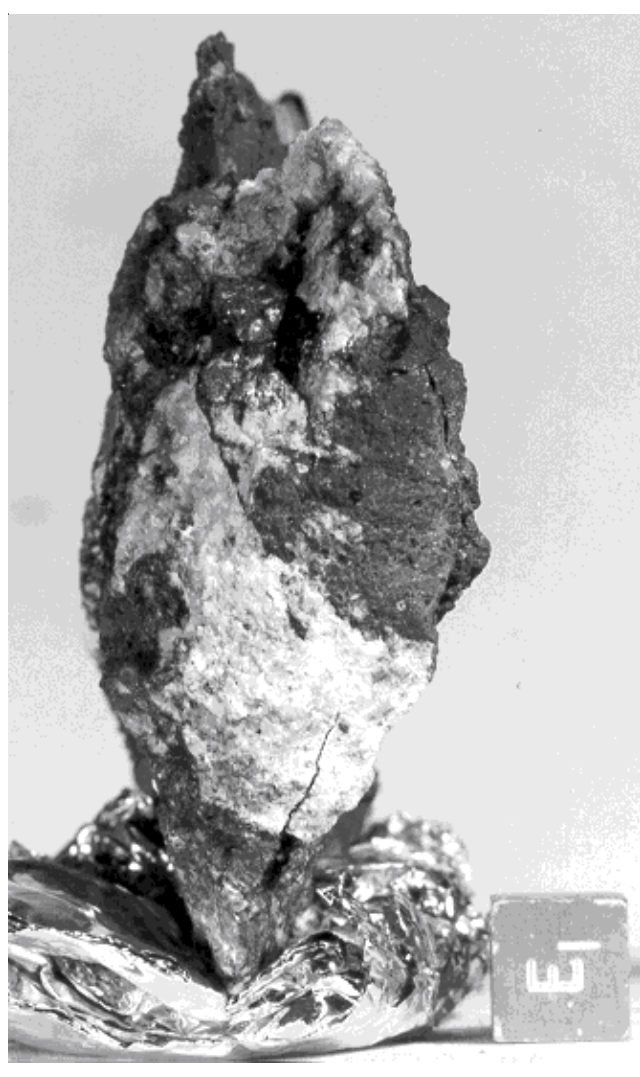

Section titled “Anorthosite Clast:”A large white “clast” of anorthosite (1 x 2 cm) is exposed on the top, bottom and east end (E1) of the sample (figures 3 and 4). It has apparently not been studied.

Mineralogy

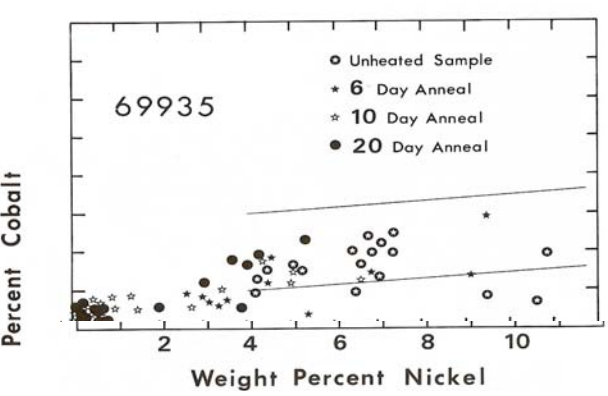

Section titled “Mineralogy”Metal: The only “mineral” that has been studied in 69935 is the Fe-Ni-Co metal grains. Taylor et al. (1976) performed annealing experiments on these grains to show that they can be significantly modified by heating – as in an ejecta blanket (figure 14).

Chemistry

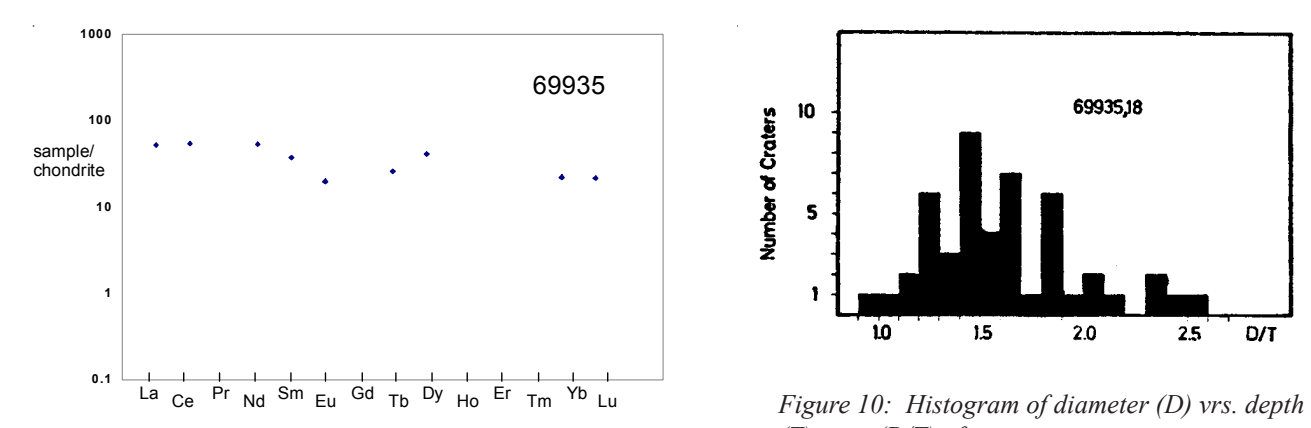

Section titled “Chemistry”The chemical composition of the matrix of 69935 is rather similar to Apollo 16 soil (either the boulder was made of soil, or the soil was made from the boulder). There is a high abundance of meteoritical siderophile elements (Ir, Au etc). The REE data in Laul and Schmitt (1973) are inconsistent with their plot, indicating a misprint (figure 7).

Radiogenic age dating

Section titled “Radiogenic age dating”none

Figure 4: Side view of 69935 showing outcrop of large white (anorthosite?) clast. NASA S72-44457.

Cosmogenic isotopes and exposure ages

Section titled “Cosmogenic isotopes and exposure ages”Behrmann et al. (1973) and Drozd et al. (1974) reported cosmic ray exposure ages of 81Kr = 1.99 and 21Ne = 1.4 m.y. - which is interpreted to be the age of South Ray Crater. The case for this to represent the age of the cratering event at South Ray crater is made by Eugster (1999).

Rancitelli et al. (1973) determined the cosmic ray induced activity of 22Na = 50 dpm/kg., 26Al = 159 dpm/ kg. and Fruchter et al. (1981) 53Mn = 135 dpm/kg. for 69935. Bhandari (1975) determined the activity of 26Al = 300 ± 140 dpm/kg. for a surface sample.

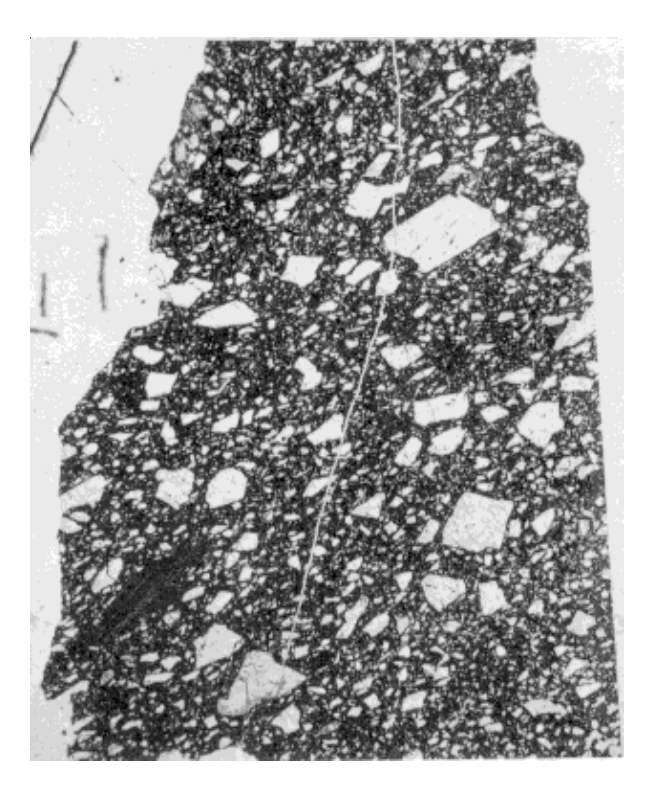

Figure 5: Thin section of glassy portion of 69935 (Ryder and Norman 1980). Width of field 1 cm.

Figure 6: Thin section of matrix of 69935 (Ryder and Norman 1980). Width of field 1 cm.

Figure 7: Normalized rare-earth-element diagram for 69935 (data from Laul and Schmitt 1973). However, this plot of their data doesn’t correspond with their plot (figure 1 Laul and Schmitt).

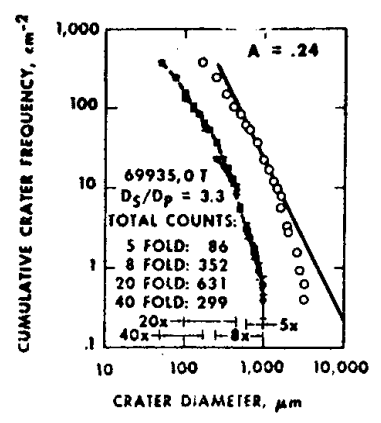

Figure 8: Size distribution of zap pits on 69935 (Neukum et al. 1973).

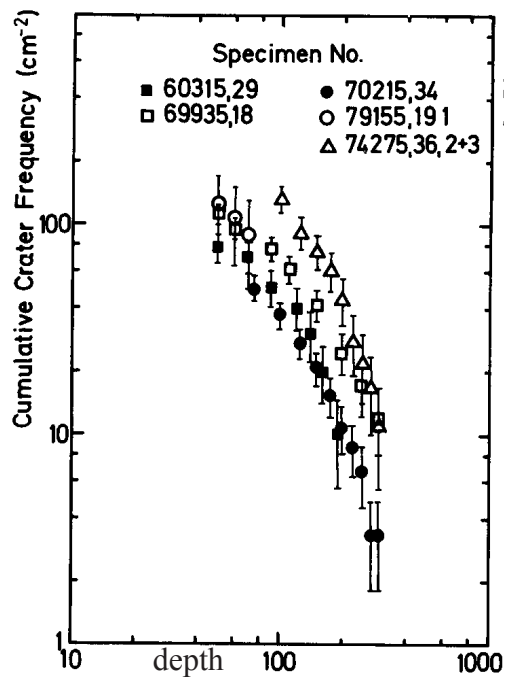

Figure 9: Size distribution of micrometeorite craters on several lunar samples including 69935 (Fechtig et al. 1974). Depth in microns.

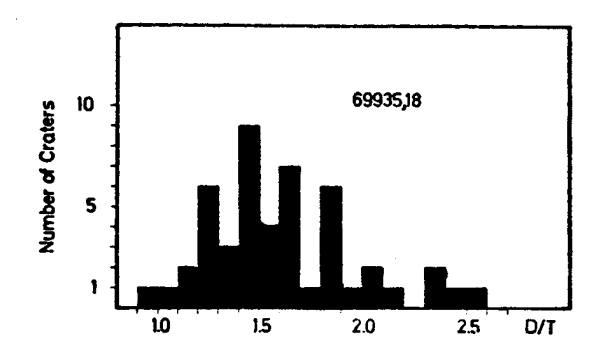

(T) ratio (D/T) of micrometeorite craters on surface of 69935 (Nagel et al. 1975).

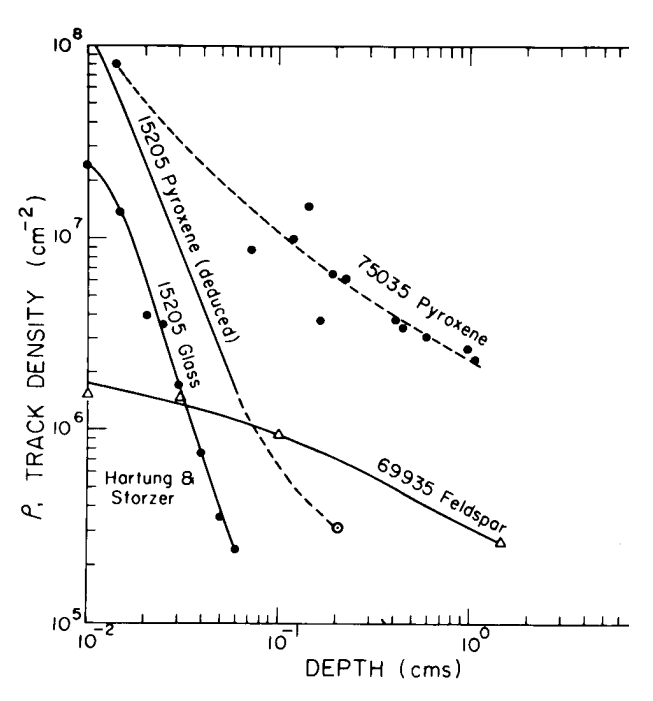

Figure 11: High energy track density as function of depth in “feldspar” in 69935 compared with track density in other rocks (Bhandari et al. 1977).

Other Studies

Section titled “Other Studies”69935 was used for the study of micrometeorite pits (Morrison et al. 1973, Neukum et al. 1973, Fechtig et al. 1974 (figures 8 and 9). Nagel et al. (1975) studied the ratio of the diameter to depth of microcraters on the surface of 69935 and compared them with other samples (figure 10). Bhandari (1977) determined a cosmic ray track density/depth profile of feldspar (figure 11) and calculated an exposure age of only ~ 0.5 m.y. (significantly less than Drozd et al. 1974) – explained by local variation in spallation of surface material.

Figure 12: Photo illustrating cm and inch-sized orientation cubes along with slab cut from center of 69935. S73-22567. Compare with figure 1.

Figure 13: The only color photo of 69935. S96-01612 Cube is 1 cm.

Table 1. Chemical composition of 69935.

| reference weight SiO2 % TiO2 Al2O3 FeO MnO MgO CaO Na2O K2O P2O5 S % sum | Ganapathy74 | Laul 73 | Rose 1973 | Rancitelli 1973 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.35 29.5 4 0.045 4 17.2 0.41 0.07 | 44.69 (a) 0.22 (a) 31.47 (a) 2.34 (a) 0.03 (a) 2.63 (a) 17.97 (a) 0.43 (a) 0.08 0.15 | (b) (b) (b) (b) (b) (b) (b) (b) (b) | (b) 0.096 | (d) | ||||

| Sc ppm V | 6 15 | (a) 5.1 (a) 16 | (b) (b) | |||||

| Cr Co Ni Cu | 583 | 472 22 (c ) 340 | (a) | (a) 15 (a) 302 3.6 | (b) (b) (b) | |||

| Zn | 0.88 | (c ) | ||||||

| Ga Ge ppb | 325 | (c ) | 1.8 | (b) | ||||

| As Se | 190 | (c ) | ||||||

| Rb Sr | 5.9 | (c ) | 2 | (b) | ||||

| Y | 42 | (b) | ||||||

| Zr Nb | 130 | (a) 130 | (b) | |||||

| Mo Ru | ||||||||

| Rh | ||||||||

| Pd ppb Ag ppb | 1.3 | (c ) | ||||||

| Cd ppb In ppb | 6.6 | (c ) | ||||||

| Sn ppb | ||||||||

| Sb ppb Te ppb | 3.63 2.8 | (c ) (c ) | ||||||

| Cs ppm Ba | 0.26 | (c ) | 110 | (a) 115 | (b) | |||

| La | 12.3 | (a) 10 | (b) | |||||

| Ce Pr | 33 | (a) | ||||||

| Nd Sm | 24 5.5 | (a) (a) | ||||||

| Eu | 1.11 | (a) | ||||||

| Gd Tb | 0.94 | (a) | ||||||

| Dy Ho | 10 | (a) | ||||||

| Er | ||||||||

| Tm Yb | 3.6 | (a) 2.9 | (b) | |||||

| Lu Hf | 0.52 3.8 | (a) (a) | ||||||

| Ta | 0.45 | (a) | ||||||

| W ppb Re ppb | 1.55 | (c ) | ||||||

| Os ppb Ir ppb | 12.7 | (c ) 8 | (a) | |||||

| Pt ppb | ||||||||

| Au ppb Th ppm | 11.9 | (c ) 8 | 2 | (a) (a) | 2.52 | (d) | ||

| U ppm | 0.87 technique: (a) INAA, (b) microchemical, (c ) RNAA, (d) radiation counting | (c ) 0.61 | (a) | 0.65 | (d) |

Figure 14: Ni and Co content of iron grains in 69935, before and after anealing.

Processing

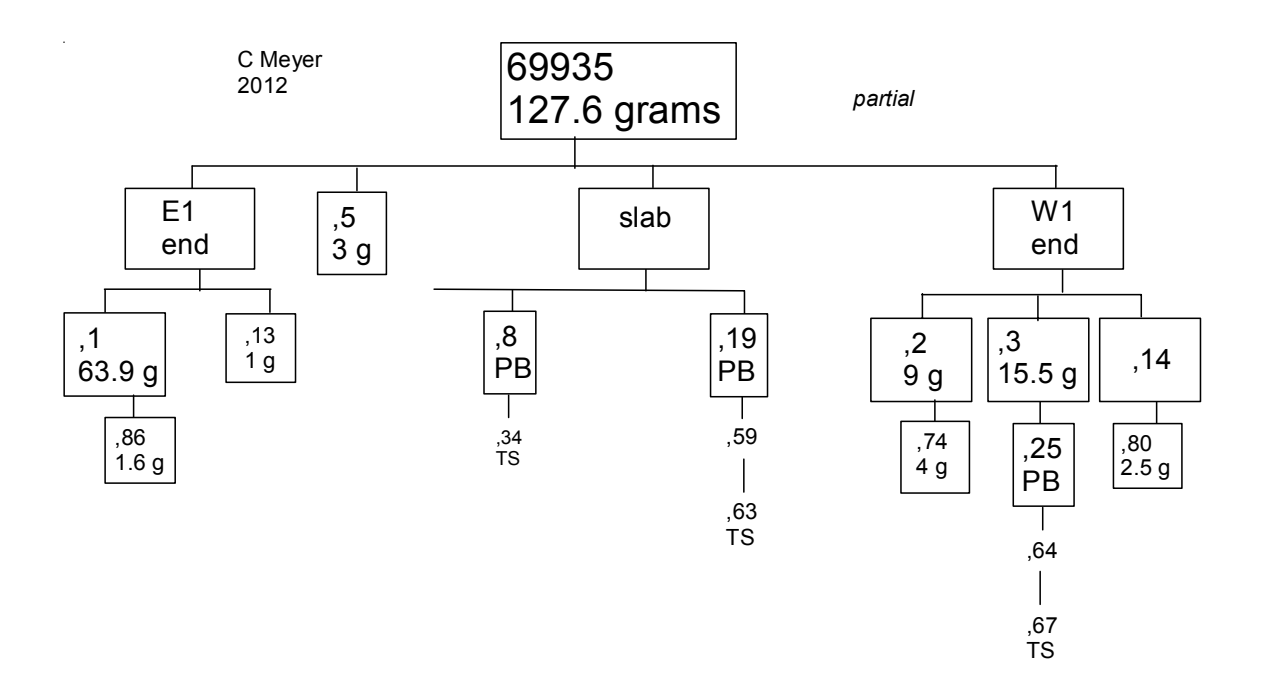

Section titled “Processing”A lab was cut through the middle of 69935 (figure 12) perpendicular to the lunar surface to obtain a depth profile. The slab only cut thru the matrix of the boulder and did not sample the large white clast (which remains unstudied). However, I see no evidence that this ideal depth profile was ever used for cosmic-ray, solar flare studies (SCR).

There are 10 thin sections of 69935.

References for 69935

Section titled “References for 69935”Behrmann C.J., Crozaz G., Drozd R., Hohenberg C., Ralston C., Walker R. and Yuhas D. (1973b) Cosmic-ray exposure history of North Ray and South Ray material. Proc. 4th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1957-1974.

Bhandari N. (1977a) Solar flare exposure ages of lunar rocks and boulders based on 26A1. Proc. 8th Lunar Sci. Conf. 3607-3615.

Butler P. (1972a) Lunar Sample Information Catalog Apollo 16. Lunar Receiving Laboratory. MSC 03210 Curator’s Catalog. pp. 370.

Drozd R.J., Hohenberg C.M., Morgan C.J. and Ralston C.E. (1974) Cosmic-ray exposure history at the Apollo 16 and other lunar sites: lunar surface dynamics. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 38, 1625-1642.

Eugster O. (1999) Chronology of dimict breccias and the age of South Ray crater at the Apollo 16 site. Meteor. & Planet. Sci. 34, 385-391.

Fruchter J.S., Reeves J.H., Evans J.C. and Perkins R.W. (1981) Studies of lunar regolith dynamics using measurements of cosmogenic radionuclides in lunar rocks, soils and cores. Proc. 12th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 567 575.

Ganapathy R., Morgan J.W., Higuchi H., Anders E. and Anderson A.T. (1974) Meteoritic and volatile elements in Apollo 16 rocks and in separated phases from 14306. Proc. 5th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1659-1683.

Hertogen J., Janssens M.-J., Takahashi H., Palme H. and Anders E. (1977) Lunar basins and craters: Evidence for systematic compositional changes of bombarding population. Proc. 8th Lunar Sci. Conf. 17-45.

Horz F., Schneider E. and Hill R.E. (1974) Micrometeoroid abrasion of lunar rocks: A Monte Carlo simulation. Proc. 5th Lunar Sci. Conf. 2397-2412.

Hunter R.H. and Taylor L.A. (1981) Rust and schreibersite in Apollo 16 highland rocks: Manifestations of volatileelement mobility. Proc. 12th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 253 259.

Laul J.C. and Schmitt R.A. (1973b) Chemical composition of Apollo 15, 16, and 17 samples. Proc. 4th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1349-1367.

LSPET (1973b) The Apollo 16 lunar samples: Petrographic and chemical description. Science 179, 23-34.

LSPET (1972c) Preliminary examination of lunar samples. In Apollo 16 Preliminary Science Report. NASA SP-315, 7-1—7-58.

Misra K.C. and Taylor L.A. (1975) Characteristics of metal particles in Apollo 16 rocks. Proc. 6th Lunar Sci. Conf. 615-639.

Morrison D.A., McKay D.S., Fruland R.M. and Moore H.J. (1973) Microcraters on Apollo 15 and 16 rocks. Proc. 4th Lunar Sci. Conf. 3235-3253.

Neukum G., Horz F., Morrison D.A. and Hartung J.B. (1973) Crater populations on lunar rocks. Proc. 4th Lunar Sci. Conf. 3255-3276.

Pepin R.O., Basford J.R., Dragon J.C., Johnson N.L., Coscio M.R. and Murthy V.R. (1974) Rare gases and trace elements in Apollo 15 drill fines: Depositional chronologies and K-Ar ages and production rates of spallation-porduced 3 He, 22Ne and 38Ar vrs depth. Proc. 5th Lunar Sci. Conf. 2149 2184.

Rancitelli L.A., Perkins R.W., Felix W.D. and Wogman N.A. (1973) Lunar surface and solar process analyses from cosmogenic radionuclide measurements at the Apollo 16 site (abs). Lunar Sci. IV, 609-612. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Rancitelli L.A., Perkins R.W., Felix W.D. and Wogman N.A. (1973b) Primordial radiouclides in soils and rocks from the Apollo 16 site(abs). Lunar Sci. IV, 615-617. Lunar Planetary Institute, Houston.

Rose H.J., Cuttitta F., Berman S., Carron M.K., Christian R.P., Dwornik E.J., Greenland L.P. and Ligon D.T. (1973) Compositional data for twenty-two Apollo 16 samples. Proc. 4th Lunar Sci. Conf. 1149-1158.

Ryder G. and Norman M.D. (1980) Catalog of Apollo 16 rocks (3 vol.). Curator’s Office pub. #52, JSC #16904

Sutton R.L. (1981) Documentation of Apollo 16 samples. In Geology of the Apollo 16 area, central lunar highlands. (Ulrich et al. ) U.S.G.S. Prof. Paper 1048.

Taylor L.A., Misra K.C. and Walker B.M. (1976) Subsolidus reequilibration, grain growth, and compositional changes of native FeNi metal in lunar rocks. Proc. 7th Lunar Sci. Conf. 837-857.